- DRC’s constitution was promulgated on 18 February 2006 following a popular referendum on 18-19 December 2005. Although the government has yet to establish all of the institutions provided for in the document, Congo retains an executive presidency and a bicameral parliament consisting of a 500-seat National Assembly and a 108-seat Senate

- While the National Assembly and president are elected by popular vote, the Senate is indirectly elected by members of provincial assemblies. Following the division of Congo’s provinces in July 2015, there should be 26 assemblies (with Kinshasa returning 8 senators, the remaining 25 provinces each proposing 4)

- Aside from the provincial assemblies, the Congolese government has yet to organise elections for governors and deputy governors, and a plethora of local government officials

- Follow developments on Twitter using the hashtags #DRCElections, #DRC2016, #ElectionsRDC, #RDC2016, #FrontCitoyen2016, #Telema, #Alternance2016

The vote scheduled to be held in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) in 2016 could mark the most significant political watershed since the presidential and parliamentary elections of 2006. Those polls marked the end of a dramatic decade shaped by complex regional dynamics, local disputes, and inter-state rivalry. Following the genocide in Rwanda, DRC endured two wars (1996-1997 and 1998-2002), with its eastern provinces becoming the frontline in “Africa’s First World War”. This vast conflict expedited the collapse of the state, ushered in a crisis of impunity and imposed inconceivable human suffering.

The 2006 vote was organised by a new electoral management body, the Commission électorale nationale indépendante (CENI), chaired by the Catholic priest, Apollinaire Malumalu. In the first multi-party polls since independence in 1960, Congolese cast ballots for a new national assembly and head of state on 30 July, with a presidential run-off held on 29 October 2006.

The victor was Joseph Kabila, who succeeded his father Laurent-Désiré Kabila as president after his assassination in January 2001. In the first round of voting, Kabila led the list of 33 candidates with 45% of the vote. His closest contender was Jean-Pierre Bemba, one of four vice-presidents, on 20%. Although Bemba managed to more than double the number of ballots he received in the second round (from 3.39 to 6.82 million), this was not enough to unseat Kabila (who received 7.59 million in the first round and increased this to 9.44 million).

Kabila was sworn in on 6 December 2006 as the first elected president of the Third Republic. Although he had stood as an independent, the Parti du Peuple pour la Reconstruction et le Démocratie (PPRD) which supported his candidacy received 111 of the 500 seats in the National Assembly; this was well ahead of Bemba’s rebel-group-come-party, the Mouvement pour la Liberation du Congo (MLC), with 64 seats. Supporters of Kabila formed the Alliance pour la Majorité Presidentielle (AMP), establishing control of over 300 seats. An upper house, the Senate, was indirectly elected by members of eleven provincial assemblies in January 2007, providing the PPRD with 22 of the 108 seats.

Despite his popular mandate, Kabila’s government was slow to repair the damage done to the Congolese state. Delays to security sector reform left the east of the country exposed to the activities of multiple armed groups. Members of Bemba’s MLC resisted their integration into the Congolese army, resulting in violence in Kinshasa in March 2007. Bemba left the country in April 2007 and was arrested by the International Criminal Court (ICC) in May 2008, accused of committing war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Central African Republic during 2002-2003. He awaits trial in The Hague.

In January 2011, the government amended the electoral code to eliminate the need for a presidential run-off, ostensibly to reduce costs. However, the vote held on 28 November 2011 stood in stark contrast to that of 2006. The sheer scale of electoral irregularities, and the degree to which results were contested, brought the country to the edge of implosion. Kabila won with 49% of the vote, but his closest challenger, Étienne Tshisekedi, leader of the Union pour la Démocratie et le Progrès Social (UDPS) refused to accept defeat and regards himself as the legitimate president. Unfortunately for him, nobody else does.

The 2011 elections should have consolidated a fragile democratic process, but they were organised by a regime whose primary concern was consolidating its own power. It succeeded in that task by exercising complete control over the state machinery (including the electoral commission, then led by a Kabila adviser, Pastor Daniel Ngoy Mulunda), enabling it to defeat a fragile and divided opposition.

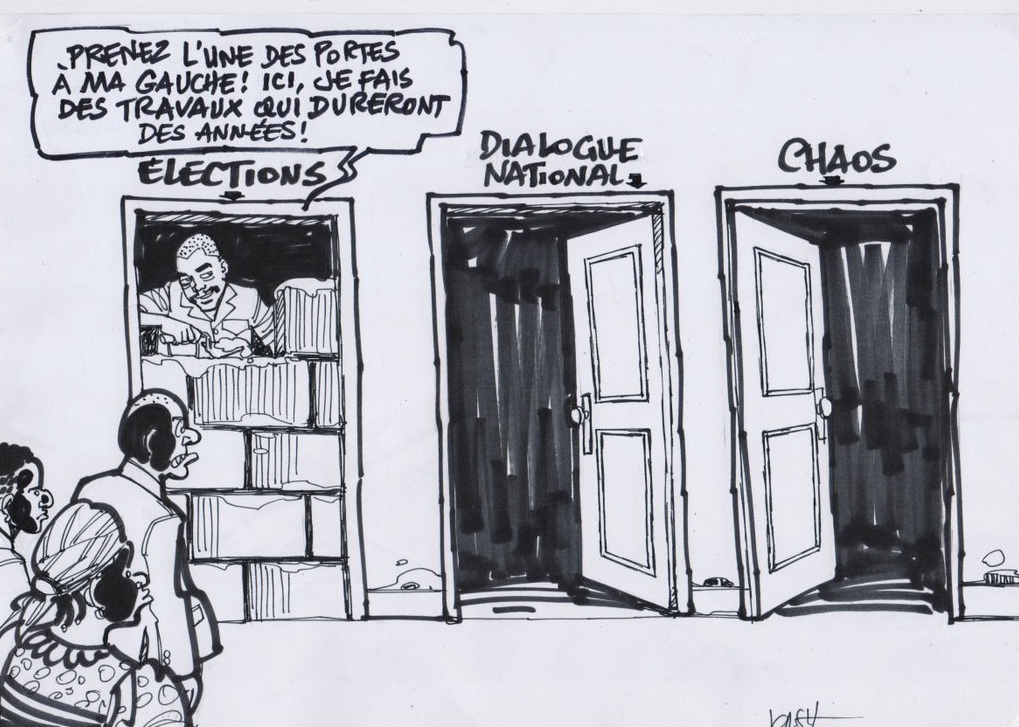

The term of office of the president and parliament will expire in December 2016. According to the constitution, the country has to have elections before the end of that year and President Kabila cannot stand for a third term. He has three main options: (a) he decides to leave office; (b) he decides to seek a new mandate; or (c) he decides to stay on under his current mandate.

Although the president has not yet officially communicated his plans, leading members of his PPRD first attempted to revise the constitution in parliament (in September 2014) before proposing an electoral law which would extend Kabila’s mandate (in January 2015). Both times they failed, initially because they did not command a sufficient majority in parliament, subsequently because of popular protests and outbreaks of violence in the cities of Kinshasa and Goma.

As time passes, tensions rise, and it becomes increasingly unclear whether it remains technically possible to organise fair and free elections within the period established under the constitution. The opposition accuses the government of glissement, or intentional slippage, a view shared by an important section of public opinion. They cite as an example the need to implement the decentralisation process: the policy of découpage, designed to divide the country’s 11 provinces into 26, was not carried out to plan in July 2015.

Questions remain regarding the capacity and independence of the CENI. Following the resignation of Pastor Ngoy Mulunda in 2013, Apollinaire Malumalu returned to chair the commission. He provided leadership at a time when the CENI was working under considerable pressure in difficult circumstances – and being systematically under-resourced by the government. In December 2014, Malumalu suffered a brain haemorrhage. He resigned as CENI chairman in November 2015 and was replaced by the relatively unknown Corneille Nangaa. Although Nangaa is considered technically competent in electoral matters, it remains to be seen whether he possesses sufficient personal courage and political conviction to guarantee the commission’s independence in the face of significant pressure.

Kabila has faced growing resistance within his AMP. In 2015, an influential group of parties (known as the G7) stated their opposition to attempts to extend Kabila’s term beyond the constitutional limit of December 2016. Leading personalities within the G7 are Pierre Lumbi, leader of the Mouvement Social du Renouveau (MSR), Olivier Kamitatu, president of the Alliance pour le Renouveau du Congo (ARC), and Gabriel Kyungu wa Kumwanza, chairman of the Union National des Fédéralistes du Congo (Unafec). However, the most likely challenger at the timing of writing appears to be the former governor of Katanga province, Moïse Katumbi, a PPRD member until 2015 who resigned in protest at plans for Kabila to remain in power. Katumbi has called for the opposition to unite behind a single candidate, to be decided via primary elections.

What remains to be seen is how these former allies of Kabila engage with his longstanding opponents. Vital Kamerhe, president of the Union pour la Nation Congolaise (UNC), sits awkwardly between the two groups, having left Kabila in 2010 and placing third in the 2011 presidential elections. Étienne Tshisekedi has not announced whether he will return to Congo for the 2016 elections. He is 83 years old and has been in Belgium for health reasons since 2014. Equally, the release of Jean-Pierre Bemba from custody in The Hague cannot be ruled out.

In December 2015, a number of opposition parties, civil society organisations and youth activists united to establish a common platform: Front Citoyen 2016. A major question for the coming months remains the degree to which the Kabila government resorts to violent repression against those campaigning for the Congolese constitution to be respected.

Kris Berwouts is an independent Congo analyst and consultant. Kris has worked on central and eastern Africa for nearly 30 years, having studied African languages and history at the University of Ghent. Until January 2012, Kris was Director of EurAc, the European network for central Africa. He tweets as @krisberwouts