Zhong Jianhua, China’s Special Representative on African Affairs, offers a direct and considered response to the charge levelled by Lamido Sanusi, Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, that China has contributed to Africa’s “deindustrialisation and underdevelopment”. He rejects any analogy between China-Africa trade patterns and those of the colonial era but agrees that Africa must regard China as a competitor pursuing its own interests. Ambassador Zhong observes many similarities between the policy choices facing African governments in the 2000s and those confronted by China during the 1980s and 1990s. He emphasises that China itself is still a developing country – and one which has a great deal to learn about Africa.

In this interview with Edward Paice, Director of Africa Research Institute, Zhong also responds to common criticisms of China’s policy and conduct in Africa. He insists that it is China’s responsibility to help African nations compete in the global economy. While acknowledging the imperative shared by all developing economies to maximise agricultural potential, attract capital, create a more skilled workforce and industrialise, Zhong is convinced that “finally the chance has come” to Africa.

What is your response to the public criticism by Lamido Sanusi, Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, to the effect that China is exploiting Africa in much the same way as the former colonial powers?

I have been asked a number of times to comment on the views expressed by Mr Lamido Sanusi in his article for the Financial Times. The majority of Western analysts and commentators have dwelt on his assertions that China “is a significant contributor to Africa’s deindustrialisation and underdevelopment” and is “capable of the same forms of exploitation as the West”. My reaction to the article was quite different.

China’s job, our responsibility, is to try and help Africa compete with us

Mr Sanusi made a very important point. He said that African countries must compete with China. This is very good. Africa is strong enough to fight economically, but this is the first time we are hearing that it is willing to do so. I welcome this kind of attitude. China’s job, our responsibility, is to try and help Africa compete with us.

In Nigeria, and elsewhere in Africa, they are in a difficult period. China has been through this process. When we decided to reform in the 1980s, under Paramount Leader Deng Xiaoping, we had such a fierce debate. Are we willing to become a capitalist society? Are we willing to allow those “evil” Western companies to come to China and make huge profits from our labour? What are we doing? These were the questions we argued about. Deng Xiaoping had to see to it personally that the debate did not become an obstacle to reform.

As a result of the economic reforms, and opening up to Japan and Western competitors, thousands of companies went bankrupt in China. They could not produce the same quality goods at a price people could afford. Millions of people were made unemployed. We learnt quite early on in the reform process that competition with established economies would be a hard battle. It was like a revolution. First, we had to reform our own industries. Only when they were strong enough could they compete. Now we are benefitting.

As a result of the economic reforms, and opening up to Japan and Western competitors, thousands of companies went bankrupt in China. They could not produce the same quality goods at a price people could afford. Millions of people were made unemployed. We learnt quite early on in the reform process that competition with established economies would be a hard battle. It was like a revolution. First, we had to reform our own industries. Only when they were strong enough could they compete. Now we are benefitting.

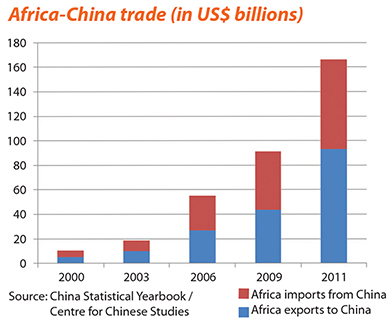

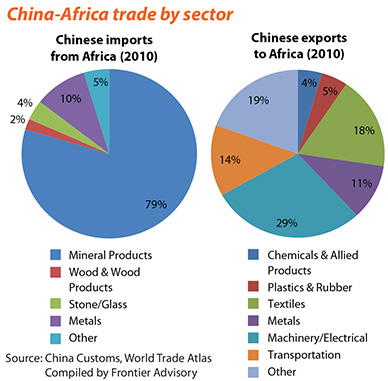

Africa may be experiencing the same frustrations as China did. Many people are angry. This is understandable. They work for many years and still don’t see the results they expected. Familiar trade patterns are still there – the export of African raw materials to the outside world, including China, and the sale of manufactured goods from China and other countries to Africa. But look at the results. If you sell oil at six cents a barrel, you can barely afford to feed yourself. This is no longer the case. Nowadays oil is US$100 a barrel and producers bring back not only food and clothing but also capital for development. Many countries have accumulated capital and are reinvesting it in infrastructure and other productive assets. Now they are on the point of take-off. This is an important difference which needs to be acknowledged, rather than just saying the trade pattern is the same as colonialism.

In time, I expect a lot of manufacturing will move from China to Africa

Every country needs a starting point. Nobody will provide lunch for free – it must be earned. It is important not to overlook this. Africa has an abundance of natural resources. If African countries want to compete, the revenues need to be managed and invested well. No country can industrialise simply by selling raw materials. At the same time, if China does not listen to their frustrations then we are forgetting our own experience. If misunderstandings arise over terms of trade with certain countries, we need to talk to each other.

As China’s competitors moved up the value chain, assembly lines eventually came to us. At the beginning of our reform and opening up we saw resources as the most important factor for high economic growth. Today, I believe that demand is even more important. Without demand, a country cannot sell its output. In time, I expect a lot of manufacturing will move from China to Africa. This is what Africa wants and it is what we want. I see no loser in this competition. We are happy to move forward together. Chinese reform and prosperity have benefitted the whole world – and African development and prosperity will also benefit the whole world.

Mr Sanusi’s comments did not surprise me at all. I work in Africa and understand both sides. To me his stance is perfectly understandable. He is an African and his love is for Africa, not for China. Of course, affection for China would be welcome, but his primary concern is the development of Africa. The international community should respect African countries by allowing them to choose their own path for development, and should believe that Africa is capable of solving its own problems independently.

On a number of occasions you have said that you are concerned that China’s “basic research on Africa is inadequate”. What is being done to remedy this?

We want – and need – to improve our understanding of Africa. This is a real challenge. The majority of official research to date has focused on developed economies or places that constitute a major concern. The Chinese business community is also too young to understand properly how to conduct operations outside China. Too often companies and investors operating abroad take domestic practices with them which can harm their prospects for doing profitable business.

Compared with their counterparts, China’s scholars are at a real disadvantage. Western scholars have been studying the continent for generations – more than two or three centuries. Their connections are far and wide. By contrast, China was not a real participant in the global economy until the late 1970s and early 1980s. Without much business in Africa, few studies were undertaken. Scholars follow commerce. We are trying to catch up, but this cannot be done overnight.

We will work with any group of people who want to understand China better – our history, aims and ambitions

Chinese scholars interested in Africa face considerable constraints. On the government side, we probably haven’t provided enough support. Scholars have complained about this. They do not have ready access to the same luxuries as Western academics who can get hold of a wide range of information with far greater ease.

We have good relations with many African intellectuals. I’ve just returned from Oxford where I had meetings with a number of distinguished scholars who understand Africa but also recognise – crucially – that China is a developing country. In my experience, the academic community has displayed a great willingness to learn about China and our relations with Africa, rather than stand aside and criticise. Our policy is simple. We will work with any group of people who want to understand China better – our history, aims and ambitions.

If the Chinese government published more data on its multifaceted ties with Africa, would it help to counter unfounded allegations and ill-informed speculation about policy?

China follows much the same policy in Africa as in the 1950s and 1960s, when we were supporting independence and liberation movements. After the 1970s and 1980s, reform and the opening up of the economy resulted in big domestic changes in China. The economy changed a lot, and fast. With all this growth, cities expanded rapidly, which of course affected China’s foreign policy.

The situation in Africa also altered in these decades. Now there is a new agenda for development, and new demands. The biggest change began in 2005 when economic growth started to improve. Finally the chance has come to this continent. Ten years ago, if anyone spoke about the future prospects for the world economy, that person would have to mention China as an emerging power. Today, any such discussion must also include Africa. People have been waiting for this for too long. Some have started to ask: after the growth of China, who will be next? Some predict Africa’s growth will overtake China’s.

Some predict Africa’s growth will overtake China’s

All this affected our foreign policy. You have to react to change. China has started to pay more attention to Africa, just like every other country in the world. We probably need to pay even more attention. The business community in China has not yet understood that Africa is the next growth area. This is why I travel across China to let people know what is happening and why China needs to invest more in Africa. I tell them that if we don’t, we will miss our chance. This is probably why President Xi Jinping visited the continent soon after becoming our head of state. In March, he was in South Africa, Tanzania and the Republic of Congo.

There is an assumption in some of the Western media – and to a lesser extent the African media – that the Chinese government has lots of data that it refuses to make public. It is important to ask the question – how accurate is the data we have? As a senior government official, I can tell you that it is not as precise as we would like it to be. When I need data, I have to go to different ministries and departments to extract it myself. If you want data, you must be prepared for a fight, and the figures I am given are not always correct. Often people have different ways of calculating things. The government’s statistical capacity is that of a developing country. At the BRICS summit in Durban, in March, our president mentioned that China has provided US$50bn of investment to Africa. It may just be an estimate. It cannot be 100% accurate.

I often hear that China’s government could mitigate much of the bad press it receives by being more transparent and publishing more data about our links with Africa. But whatever we do we will never please those who are determined not to see any good in China. Some of them have such a hostile attitude.

China may shed tens of millions of manufacturing jobs in the next decade as it moves up the value chain and domestic wages rise. Will Africa secure a share of these jobs?

The market is the dominant force in the global economy. There is generally a low cost of labour in Africa. But the biggest challenge is to create a skilled labour force. When I was ambassador in South Africa, I was puzzled to see the government establish one programme after another for skills training. Millions of rands were spent on this – the government was desperate to train its people in order to attract industry to the country.

The market is the dominant force in the global economy. There is generally a low cost of labour in Africa. But the biggest challenge is to create a skilled labour force. When I was ambassador in South Africa, I was puzzled to see the government establish one programme after another for skills training. Millions of rands were spent on this – the government was desperate to train its people in order to attract industry to the country.

China also had a huge population of peasants in the 1970s. I was one of them. But in China, we just moved peasants straight into factories. When they arrived they didn’t have any skills. They knew about agricultural labour but had no idea about factory work. It was the responsibility of businesses to train them. Companies know exactly what kind of skills they need, what kind of workers they need, and they train them in the most economical way to meet their specific requirements. Can we not encourage more of this in Africa? Taking workers out of the classroom and training them on the assembly line?

Of course, you need a core group of skilled workers to do the training. We should try a lot of different approaches to get this right. I always tell Chinese companies coming to Africa, don’t just bring Chinese labour with you. If you think local staff are not skilled enough – train them. Bring together the skilled and non-skilled workers, just like we did with the TanZam railway in the 1970s – 60,000 Chinese workers trained 100,000 Africans. We need to do more of this.

A clever and wise investor can make high margins and significant profits in Africa

In the competition for jobs, investment is as important as skills. I read a book called The Architects of Poverty by Moeletsi Mbeki, the brother of the former President of South Africa. I know it is a controversial book. He says that for the past few decades, when African countries and individuals have accumulated capital they have preferred to invest it in Europe or America. You cannot criticise this – capital always goes after profit – but it has hampered economic development and diversification.

What I see now is capital being attracted to Africa from China. A clever and wise investor can make high margins and significant profits in Africa. I am always having conversations with entrepreneurs who are interested in coming to Africa. Quite a famous Chinese businessman in food processing has just told me he has chartered a plane to visit South Africa next month – he has spotted an opportunity. This continent is attractive to capital and that will encourage development.

Agriculture is the principal livelihood in most African economies. What lessons are there from China for the sector’s role in driving economic growth and industrialisation?

It is not up to me to give lessons to African countries, but I can share China’s experience.

In China, food is central to everything. “Have you eaten yet?” is a common greeting. For centuries, the most important question that any ruler of China had to answer was whether they could feed the people. The Chinese government still regards agriculture as its principal priority. At the beginning of each year the first instructions set by the Communist Party of China relate to agriculture. We never stop reforming our agricultural and rural policies.

I think that many African leaders ask themselves the same questions as we do in China. But our experience cannot be replicated in Africa. The context is totally different. Africa is home to 60% of the world’s uncultivated land. China, on the other hand, is an overpopulated country with limited agricultural land. We sometimes put 100% more labour into a field in order to achieve a 5% increase in production. Survival, not productivity, is the primary concern. Without the 5% extra output, there is no safety net. If an agricultural disaster occurs which wipes out the year’s harvest, then the population at large will starve. How can people survive until the next harvest? That is the reality in China.

There are some parallels between China and individual African countries. For example, Rwanda, like China, has a large population relative to its agricultural and land resources. In both countries, agricultural capacity struggles to keep pace with population growth and each piece of land must be used effectively. But most African countries do not suffer from shortage of land. Agricultural development should be different from China’s.

When land reform occurred in China, and the land was taken away from landlords and given to the peasants, they worked the land in the same way as they always had. The vast majority of landholdings were small – family-sized – when China embarked on agricultural reform. The system of production did not change much. It was not completely disrupted by reform. In one particular African country, however, an industrialised agricultural economy existed. When land was transferred to smallholder farmers, they did not possess the skills or knowledge to run a modern farm and they received too little support. The result was that many new farmers were unable to carry on with agricultural production, and ended up selling farm assets.

Self-sufficiency in food production is a model of the past for farmers

It is a big challenge for Africa to undertake agricultural and land reform. Various experiences show that it is never a straightforward process. If African countries were to copy China, they would almost certainly fail. My advice to Chinese experts when they say they are going to tell people how to do farming in Africa is that they must study the environment – the local conditions – first. Solutions differ from country to country, and they must come out of the experience of the African farmers. We can help and collaborate with them, but we should not tell them how to farm.

We are learning and trying to find the correct way to invest in African agriculture. I don’t think we have discovered the correct way yet. For example, I administered a flawed project when I was the ambassador in South Africa. We helped to establish a training centre for farming fresh water fish. But we failed to investigate properly whether people in South Africa actually eat fresh water fish. In general, they are smaller than sea fish and notorious for their small bones. It became clear that there was not as big a market for these fish as there is in China. In each country, markets are different and consumers have different preferences. If the market does not exist, any agricultural initiative is likely to fail.

Agriculture is a commercial activity. Farmers must find markets for their produce. Self-sufficiency in food production is a model of the past for farmers. In modern agriculture, farmers must respond to what the market demands. This is a big challenge. China does not have all the answers or experiences to share with people. But we are trying to learn.

The commonly heard phrase “China in Africa” can imply a high degree

of central co-ordination of trade and investment flows – and even the

movement of people – by the Beijing government. To what extent is such

an impression erroneous?

It is impossible to co-ordinate all these things, even if we wanted to. China is a developing country. The government in Beijing sometimes appears very capable, but in fact when we have tried to control foreign investment and trade we have found that it is impossible. Even for Western countries it is not possible – can you control the activities of all your people abroad?

China is neither bad nor good. China is a combination of these things

China is a huge country with so many provinces, cultures and traditions. When people generalise about China, I say to them, “the ‘China’ you are talking about does not exist. You must be precise”. When referring to the Chinese government, you must be clear about which government – provincial, local or central – and which activity. You cannot generalise and say “this is China in Africa”, any more than you can say “China is good” or “China is bad”. China is neither bad nor good. China is a combination of these things.