Eritrea and Rwanda are among Africa’s smallest and poorest states. Substantial military resources, and expertise, have enabled both countries to exert disproportionate influence over regional security. Aggression and authoritarianism have not prompted matching responses from donor nations. While President Paul Kagame’s leadership of Rwanda has been championed as “visionary”, President Isaias Afwerki is accused of transforming Eritrea into a rogue, pariah state. These notes argue that popular perceptions of these comparable, though seldom compared, countries have been simplistic – and polarised.

Nascent states

In the mid-1990s, the survival of Eritrea and Rwanda as viable states was in doubt. At independence in 1993, Eritrea’s infrastructure and economy lay in ruins after thirty years of “armed struggle” with Ethiopia. In 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) took control of a country in which 800,000 people had been murdered in three months. Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki and RPF military commander Paul Kagame were touted as exemplars of a new generation of African leaders – disciplined, capable and incorruptible “soldier princes”.

With the demise of Mengistu Haile Mariam’s Derg regime in Ethiopia, Eritrea’s prospects were buoyed by the likelihood of an enduring peace with its neighbour. Visitors to Asmara admired the prevailing sense of purpose and resourcefulness, the absence of corruption or crime, and the orderly demobilisation of tens of thousands of Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF) fighters as much as the beauty of Eritrea’s capital city. Africa’s newest nation attracted commitments of more than US$1 billion of development and humanitarian assistance in the 1990s (1). The Eritrean economy grew rapidly, if unevenly. A new constitution, the prominence of women in politics and civil society, and the promise of democratic elections boded well for a country dubbed “the hope of Africa” (2).

Rwanda’s recovery was more problematic, and precarious. Genocide was succeeded by a civil war mostly prosecuted on foreign soil. Rwandan forces invaded the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – then called Zaire – in 1996, to counter the threat posed by exiled genocidaires. As Eritrean troops were sent to assist the new regime in Rwanda, political commentators referred to an emerging “Asmara-to-Kigali axis”(3) of power. The invasion culminated in the overthrow of Zaire’s pro-Hutu President Mobutu and installation of Laurent-Désiré Kabila in his stead.

In 1998, seven years of peace between the post-Derg governments in Eritrea and Ethiopia ended abruptly. Simmering tensions between the former allies were unmasked by a series of minor border incidents, and Eritrea’s decision to replace the Ethiopian birr with its own currency, the nakfa. As if emboldened by Rwanda’s seemingly successful tilt at becoming the leading playmaker in Central Africa, President Isaias rejected attempts at mediation by RPF leader Paul Kagame and the United States. Three phases of vicious fighting cost the lives of more than 70,000 Ethiopian and Eritrean combatants – and more than a billion dollars – before an uneasy peace was restored in 2000.

Also Read: How Rwanda judged its genocide?

As Eritrea and Ethiopia went to war in 1998, Rwanda troops re-invaded DRC – and remained there until 2002. Despite widespread criticism of the conduct and intentions of Rwandan troops in DRC, Kigali began to attract the plaudits once bestowed on Asmara. After becoming president in 2000, Kagame earned increasingly voluble praise for maintaining stability in Rwanda, overseeing economic recovery, and implementing a truth and reconciliation process through traditional Gacaca courts. In 2009, Rwanda was welcomed into the Commonwealth as its 54th member state.

“Building a nation from nothing? A nation that has just experienced a genocide? There is no strategy manual for this.” – President Paul Kagame (4)

States of emergency

The Eritrean and Rwandan presidents have countered adversaries, internal and external, with conspicuous aggression. The imposing statue of a huge pair of shida– the distinctive sandals worn by EPLF fighters – in Asmara, and the Genocide Memorial Centre in Kigali, enshrine the legacies that define the two nations. President Isaias has been no more combative than his Rwandan counterpart. But he has proved less diplomatically adroit at containing international objections to his conduct.

Eritrea has spent a decade fully mobilised. The perceived threat of Ethiopian expansionism, spearheaded by late Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, has dominated President Isaias’s foreign and domestic policy. Ethiopia’s refusal to allow physical demarcation of the border with Eritrea, in keeping with agreed peace terms, exacerbated Eritrean concerns about their neighbour’s intentions. Once a committed ally of the US, and member of President George W Bush’s coalition of the willing, Eritrea has since been portrayed as a malevolent regional spoiler. For his part, President Isaias has been cast by his fiercest critics as delusional and megalomaniacal.

Eritrea’s objection to Ethiopia’s non-compliance with agreed peace terms is legitimate. But its diplomatic efforts to secure compliance were heavy-handed, and short-lived. In Eritrea, the border impasse evokes bitter memories of the UN’s decision to promote the federation of Eritrea to Ethiopia in 1952, and international indifference when Ethiopia forcibly annexed the former Italian colony a decade later. In the absence of an enforced insistence by the UN or US that Ethiopia must allow physical demarcation of the border, President Isaias contends that continued opposition to Ethiopia by any means is justified – and a matter of national survival.

President Kagame evinces equal scorn for the UN, citing its failure to intervene resolutely during the genocide. The inertia displayed by the international community is further blamed for allowing UN refugee camps in eastern DRC to be taken over by exiled soldiers and Hutu militias who had carried out the genocide. Rwanda’s armed forces have made at least four major incursions into eastern DRC since 1998, and have supported pro-Tutsi rebel groups. For Kagame, the perpetrators of genocide still imperil Rwanda’s stability, and future. Their crime, he argues, has merited exceptional responses.

UN allegations that Rwandan commanders and troops may themselves be guilty of genocidal crimes in DRC are rejected outright by President Kagame. Accusations that Rwanda’s incursions were accompanied by the systematic looting of Congolese natural resources have also been parried with disdain. Despite some criticism from foreign governments, including those of the US and Britain, Kagame has enjoyed the support of successive US presidents and other world leaders. Astute diplomacy – backed by frequent reminders of the genocide – has secured international forbearance, though not approval, for Rwanda’s pugnacity.

My way

From the outset, the presidents of Eritrea and Rwanda have emphasised their zero tolerance for corruption, and commitment to gender equality, education and good government. Vigorous development programmes in both countries have been driven by authoritarianism. Dissent and ethnic or religious divisionism are not tolerated in either country. Power is concentrated in the hands of the president and a small circle of senior advisers and military commanders. Arbitrary arrests, disappearances, and politically-motivated prosecutions are commonplace. Political competition and critical reporting have been smothered. Human rights groups have criticised Rwanda and Eritrea in equal measure.

In Eritrea, the principle of political pluralism is enshrined in the constitution. But since the protest by the so-called “Group of 15” senior ministers in 2001, opposition to the president has been divided, ineffectual, and mostly directed from abroad. President Isaias cites “participation in the life of the country”(5) as the measure of Eritrean democracy. There are, he asserts, numerous fora through which Eritreans are publicly consulted and can air grievances. But the tens of thousands of refugees who have fled Eritrea since 2000 have, paradoxically, been cited as evidence that the country is a prison state. The US State Department ranks Eritrea as the country with the worst human rights record in the world.

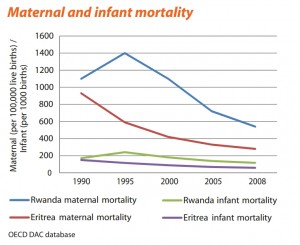

Also Read: Diehards and Democracy: Elites, inequality and institutions in African elections

The Eritrean government’s commitment to development is longstanding, and genuine. Donor assistance has mostly been withdrawn, or rejected for being profligate and of no use. In 2005, amid worsening relations between their two countries, Eritrea asked the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) to cease operations in the country. But Eritrea has been praised by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for “commendable progress … in primary education and health, as well as in infrastructure development”(6). The country is one of only four in Africa likely to achieve the Millennium Development Goal (MDG) for maternal health, and one of a handful which met the “roll back malaria” targets set by the 2000 Abuja Declaration.

“You go and ask the Chinese [about] their democracy.” – President Isaias Afwerki (7)

President Kagame has been as proficient as President Isaias in silencing domestic critics and opponents. International calls for greater political pluralism are dismissed as an example of western double standards. Kagame maintains that the political process in Rwanda is fully inclusive. An annual assembly known as the National Dialogue is described by the Rwandan press as “the epitome of citizen participation” (7) in government. Turn-out in elections is always high. RPF loyalists affirm the existence of a national consensus on the undesirability of multi-party elections. The suppression, as opposed to accommodation, of ethnic identities is understandable – but fraught with hazard. Hutus comprise 85% of the population, yet the Tutsi-dominated RPF secured four-fifths of the elected seats in parliament in 2008.

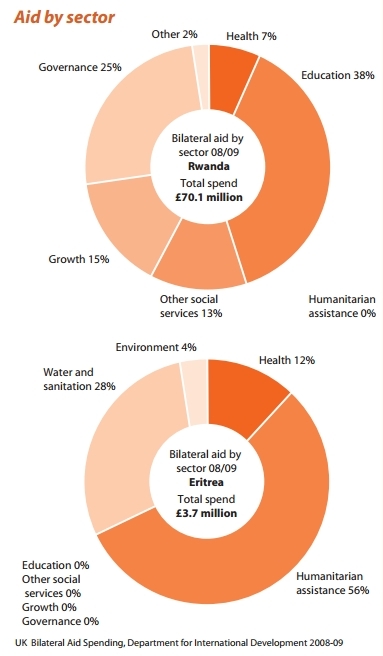

Rwanda has usurped, and exceeded, Eritrea’s popularity with international donors in the 1990s. The country is routinely upheld as a model for post-conflict reconstruction, and was selected by international donors as a test case for general budget support. In 2005-09, Rwanda received almost US$2 billion of overseas development assistance – five times the amount granted to Eritrea (9). Rwanda, like Eritrea, is on track to achieve six of the eight MDGs by 2015. President Kagame’s distaste for aid, insistence on self-reliance, and forthright handling of donors have matched those of President Isaias. But Rwanda will remain heavily dependent on donors for the achievement of its Vision 2020 national development plan.

Command economies

Subsistence agriculture is the predominant livelihood in Eritrea and Rwanda. In both countries, economic management is highly centralised and members of the ruling party dominate the private sector. But economic performance has followed different trajectories. In 2004-08, Rwanda recorded 8.6% average annual GDP growth while Eritrea’s per capita GDP contracted by an average of 5.2% annually (10). Rwanda has been referred to as the future Singapore of Africa. The Eritrean government’s economic strategy has been likened to that of North Korea.

The 1998-2000 war with Ethiopia, and continuing mass mobilisation, have had severe consequences for the Eritrean economy. Before the conflict, Ethiopia was the market – now closed – for two-thirds of Eritrea’s exports. A decline in international development assistance, and negligible foreign investment, have further handicapped economic progress. Attempts to promote growth in agriculture, tourism, construction, fisheries and ports have met with limited success. Remittances from the Eritrean diaspora, voluntary and government-enforced, are equivalent to about one third of national GDP.

Natural resources have provided President Isaias with an economic lifeline. A gold, zinc and copper mine valued at US$1.5 billion – a sum greater than Eritrea’s annual GDP – commenced commercial production in January 2011. The Eritrean government holds a 40% stake. Progress by international mining companies towards extraction of many other mineral assets, including potash deposits acknowledged as world class, is well advanced. Eritrea’s coastal waters are being surveyed for oil and natural gas. Forecast GDP growth of 17% in 2011 will make Eritrea the world’s fastest growing economy (11). After a decade of economic marginalisation, President Isaias has declared his intention to “strengthen diplomatic activities focusing on trade and investment opportunities” (12).

Rwanda’s recent economic performance has been praiseworthy, and encouraging. By 2017, when his current term expires, President Kagame intends to transform Rwanda into a middle-income “knowledge-based economy” by exploiting competitive advantages in information and communications technology (ICT), horticulture, tourism, tea and coffee. A marked improvement in agricultural production ensured that the country grew as much food as it consumed in 2009, for the first time since the genocide. Future growth requires diversification, and new sources of employment. Rwanda is Africa’s most densely-populated nation. At the current rate of expansion, the population will have doubled in 2006-16 – and will double again by 2035.

The achievement of President Kagame’s economic ambitions requires very high levels of foreign investment. Major infrastructure projects have attracted funding, including a modern rail link with Burundi and Tanzania, and a new international airport at Bugesera. Much more is planned – Rwanda needs US$4 billion to extend access to power to 50% of the population by 2017. Investment flows will be more acutely sensitive to confidence in Rwanda’s stability, and its president, than international development assistance.

The tortoise and the hare

Eritrea and Rwanda exert considerable influence in regions often described as troubled – the Horn of Africa and Great Lakes. As former soldiers, President Isaias and President Kagame seem more at ease amid continuing states of emergency – real or prospective – than with peacetime government. But common stereotypes of the two leaders are injudicious, and coloured by convenience.

President Isaias’s fall from international favour has been rapid. In 2003, Eritrea was regarded as a key frontline state in the US-led “war on terror”. Subsequent isolation was both self-imposed – motivated by anger at international inaction and perceived injustice – and externally inflicted. Attempts to counter Ethiopian hegemony severely damaged Eritrea’s international relations. But the first signs of détente are discernible.

In 2010, President Isaias strengthened Eritrea’s ties with Qatar, China, Egypt, Oman and Iran. Natural resources have endowed the president with a gilt-edged, arguably face-saving, calling card. Significantly, Eritrea resumed links with the AU in Addis Ababa. Relations with neighbours Sudan and Yemen – base of Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), labelled “the greatest single terrorist threat to the security of the US” (13) – are good. A resumption of constructive dialogue with the US may not be imminent. Eritrea’s national motto is akay’da bobi’ye, “at a tortoise’s pace”. But a thaw in US-Eritrea relations would considerably enhance regional stability.

Moral outrage at Rwanda’s genocide, and guilt at the failure of the international community to stop it, have underwritten the high level of support for Rwanda – and President Kagame. In marked contrast to President Isaias, Kagame has successfully mobilised a host of former premiers, globally-influential businessmen and celebrities on Rwanda’s behalf. Prominent journalists and academics have lauded Kagame in the 2000s as they did Isaias in the 1990s.

President Kagame’s domestic popularity should not be under-estimated. But external criticism of the Rwandan leader intensified during 2010. Publication of the UN Mapping Report on possible infringements of humanitarian law by Rwandan troops in DRC since 1993 exacerbated growing unease. International reactions to the degree of autocracy on show in the run-up to the presidential elections were measured. Rwanda remains a more fragile state than Eritrea. Threats to stability, both internal and external, loom larger than any confronting Eritrea – and are potentially far graver.

The presidents of Eritrea and Rwanda have much in common. Neither has sought personal gain from office. Both are quick to castigate outside interference. Violence is readily deployed to defend national interests and independence. Marked authoritarianism accompanies constructive development. Donor nations and organisations have by turns been ridiculed, lambasted and embraced by both presidents. Traits displayed in the 1990s, when both presidents were lauded, remain to the fore. More considered, evolving renderings of the two leaders are to be welcomed.