October 2012

China has re-cast Africa’s position in the global economy. Africa’s natural resources and China’s “Go Out” strategy have underpinned a rapid surge in Chinese investment and two-way trade. The array of Chinese enterprises active in Africa, and their financing, defies simple categorisation. China’s adherence to principles of “non-interference” and “mutual benefit” is increasingly tested as ties multiply and expectations rise. These notes argue that African governments should collaborate more keenly in exploiting relationships with China – and other trading partners – to improve economic diversification and competitiveness.

Going global

Sino-African ties proliferated during the 2000s. Popular depictions of the relationship are polarised. China’s presence in Africa is typically cast as an unalloyed blessing or neocolonialist curse. During a seven nation tour of Africa in August 2012, the American Secretary of State Hillary Clinton implied that China’s interest in Africa is motivated solely by a desire to profit from its natural resources. Burgeoning links with countries not rich in oil and metals – from Malawi to Senegal – undermine allegations of an exclusively extractive agenda. Politically charged pronouncements, like popular depictions, disregard the diversity of interaction between multifarious Chinese enterprises and African countries.

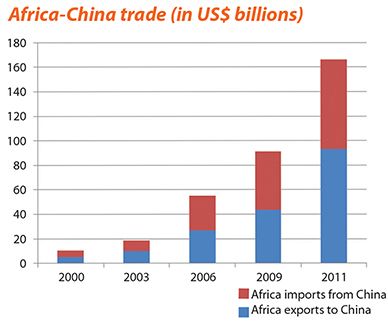

The acceleration of Chinese economic engagement with Africa is striking. Foreign direct investment increased thirty-fold between 2003 and 2011, from US$491m to US$14.7 billion. In 2012, China pledged US$20 billion of loans to Africa over three years for infrastructure, agriculture and manufacturing. If the funds are committed,

China will become Africa’s principal financial backer. China is already Africa’s leading bilateral trade partner. Two-way trade grew from US$10.6 billion in 2000 to US$166 billion in 2011.

The association of the Communist Party of China (CPC) with Africa has a long history. During the Cold War, strategic alliances were forged with liberation movements and newly independent African states in an effort to counter American and Soviet influence – and diplomatically isolate Taiwan. The 1,860km TAZARA railway was the most conspicuous manifestation of Chinese assistance in this era – and, at US$500m, the most costly. In the 1980s and 1990s, China’s foreign policy objectives were gradually realigned to underpin ambitions for domestic economic growth. China’s “Go Out” strategy, initiated in 1999, was framed to secure access to natural resources and encourage domestic companies to become globally competitive. Overseas investment and aid are utilised to promote industrial growth and diversification. The Beijing government has been reluctant to promote a “China model” for Africa – or elsewhere.

Although Africa policy is still decided at the highest level of the CPC, it is implemented – and shaped – by organisations pursuing varied, sometimes competing, objectives. Globalisation has entailed a diminution of central control over Chinese concerns operating overseas. State-owned and private enterprises compete with each other for mining and construction contracts. Sudanese oil extracted by the state-owned China National Petroleum Company is sold on international markets to the highest bidder. Provincial administrations and private companies attracted by the margins attainable in Africa have forged their own presence in resource extraction, infrastructure construction and consumer markets – accounting for a quarter of Chinese investment in the continent by 2007 (1). Chinese traders independently seek new markets for exports and low-cost production.

Enthusiasts for China’s growing involvement in Africa are united in their antipathy to the modus operandi of western donors and multilateral financial institutions. African government ministers praise China for a “can do”, non-prescriptive approach. Chinese officials and investors have criticised western governments and donors for being

out of touch with the needs of contemporary Africa. As Sino-African ties become increasingly complex and entrenched, the Chinese government will face dilemmas created by economic relationships it does not fully control. “Though China is an officialdom-led society. . .a national level synergy is not feasible in Africa, or we could return to the old track of colonialism”, remarked Zhong Jianhua, China’s special envoy to Africa, in April 2012 (2).

Africa belongs to the Africans – it is not anyone’s ‘cheese’ – Zhai Jun, deputy foreign minister of China (3)

Aid and financial flows

Multi-billion dollar commodity-backed infrastructure loans from Chinese banks to African governments have gained notoriety for a lack of transparency. China is frequently accused by western governments and corporate competitors of using aid to promote commercial interests and “resource colonialism” – and of encouraging corruption. Many charges of impropriety are simplistic or politically motivated. The heterogeneity of China’s financial transactions with African

counterparts is often overlooked.

The negotiation of loans secured against revenue from natural resources is modelled on the practice of Japanese firms investing in China in the 1970s. Interest rates are almost always non-concessional. For the Chinese government, and its African partners, these are straightforward commercial transactions. Sovereign entities, both sides often argue, are as entitled to confidentiality regarding terms as any corporate investor. But massive loans to African governments raise genuine concerns about repayments – and beneficiaries.

State-backed “policy banks” – including the Export-Import (Exim) Bank of China and China Development Bank – promote government interests. In addition to providing non-concessional finance for infrastructure loans, Exim Bank offers concessional loans with discounted rates, interest payment “holidays” and long repayment periods. But most of China’s financial institutions take advantage of China’s colossal foreign exchange reserves and low global interest rates to offer competitive, as opposed to state subsidised, credit to Chinese companies and African governments.

Also Read: China in Africa: five lessons from ODI

The conduct of most leading financial institutions from communist China which are active in Africa differs little from that of their capitalist western peers. The US$3 billion government-backed China-Africa Development Fund (CADF), launched in 2007, invests in Chinese companies keen to pursue long term ventures – and higher returns – in Africa. In 2008, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China purchased 20% of South Africa’s Standard Bank for US$5.5 billion. Increasing equity investment in Africa by Chinese companies and financial institutions is indicative of a progression from the export of goods to the export of goods and capital.

Aid, like trade and investment, is one of an assortment of tools deployed in the pursuit of China’s economic and political objectives. But only a modest proportion of total Chinese funding in Africa conforms to common definitions of “aid”. In 2009, an estimated US$1.6 billion of grants, interest-free and concessional loans, and preferential lines

of credit were disbursed for largely diplomatic purposes (4). Most Chinese finance in Africa is investment – for profit. Export buyers’ credits, commodity-secured export credits and commercial loans support the rapid expansion of Sino-African trade.

Trading places

Intense competition for jobs in China has forced many to seek economic opportunities abroad. More than 2,000 investors and businesses have operations in Africa. Estimates for the number of Chinese living on the continent range from 500,000 – 1 million, although records are unreliable and migrants regularly overstay temporary visas. Contract workers employed by state-owned and large private corporations seldom encounter Africans outside the workplace. For the vast majority of Africans who do come into contact with Chinese, interaction is with small-scale traders and business owners with no sponsorship or support from Beijing.

Chinese traders have caused discontent in local markets. In Uganda, retailers closed their shops in protest at being undercut by competitors and cheap goods from China. African authorities have responded to popular demands for greater regulation. In Malawi, foreign traders are restricted to establishing businesses in the four main cities. Botswana introduced a list of professions reserved for nationals. Africa is not a first-choice destination for Chinese migrants. Profit margins in local markets are usually small, and existence precarious. Poor quality goods and strict no return policies have provoked widespread demands for better regulation of Chinese imports. Concerns about reputational damage have prompted officials in Beijing to address quality control. In 2012, at the Fifth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC V), the director-general of China’s Department for Africa declared that goods “must go through a special inspection to ensure only those with high quality” are exported.5 Specific measures to guarantee standards and protect local industries in Africa were not articulated. A proposed code of conduct designated trading standards “a matter of ethics rather than law” (6).

The refrain that Africa is a dumping ground for unwanted Chinese products largely disregards the active role of African consumers. More often than not, supply is generated by demand. Chinese market traders peddle affordable consumer goods. In many wholesale markets, Chinese businessmen rely on African agents to identify what will sell

locally. As supply chains multiply, and more African entrepreneurs travel to China to source goods directly from manufacturers, the influence of African consumers on the type of goods imported from China will continue to increase.

“Win-win” reconsidered

Chinese government officials emphasise the role of China in “supporting African countries to choose their own development path” (7). Triennial FOCAC conferences aspire to align the interests of China and Africa. The discourse of the “mutual benefit” of economic relations is increasingly accompanied by insistence that the Beijing government must do more to reconcile official rhetoric with actions. For Africans, the continued plausibility of claims on both sides of the uniquely reciprocal and developmental character of China-Africa relations will depend on the prompt delivery of more discernible – and widespread – benefits.

The World Bank estimates that the Chinese economy will shed 85m jobs by 2022 as it “moves up the value chain” and workers demand higher wages and better living standards. A growing number of Chinese manufacturing companies are assessing Africa as a potential site for low-cost production. Seven to ten million people enter the labour market each year in Africa. Duty-free and tariff-free access to American and European markets through the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) and Cotonou Agreement remain underexploited incentives to manufacturers. But as yet the transfer of jobs from China to Africa remains illusory.

Africa’s past economic experience with Europe dictates a need to be cautious when entering into partnerships with other economies” Jacob Zuma, president of South Africa (8)

A more prevalent reality in Africa than new jobs is the collapse of small and medium enterprises under pressure from cheap imports. According to one study, competition from Chinese imports may have cost South Africa 78,000 industrial jobs in 2001-10 (9). A Chinese currency undervalued by anything up to 40%, according to common estimates, keeps domestic production costs low – and has prompted accusations that China is “exporting unemployment”, not jobs, to Africa (10). Significant demand for light manufacturing jobs still exists within China. Furthermore, African countries face stiff competition in the global labour market from the likes of India, Bangladesh, Mexico, Turkey and Vietnam.

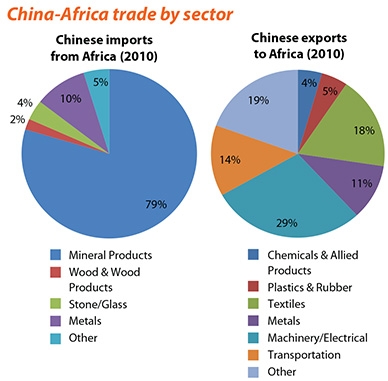

While Africa showed a US$20 billion trade surplus with China in 2011, more than three-quarters of the continent’s exports are oil, gas, metals and minerals from five countries – Sudan, Angola, Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa. Chinese exports to Africa are far more diverse – by destination and product. Excluding oil exports, Africa had a trade deficit with China amounting to US$28 billion in 2011 (11). In the 2000s, Sino-African trade was not accompanied by significant skills development, technology transfer or productivity improvements in Africa. Of eight economic and trade co-operation zones approved by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce in 2006, only one – in Egypt – was fully operational by 2012. At FOCAC V, China announced plans to remove tariffs on 97% of items from 30 least developed African countries, and pledged to train 30,000 workers and provide 18,000 scholarships. Repeated affirmations from the Chinese government of the intention to bolster regional trade, link African products to global supply chains, and improve the variety of imports and the quality of exports remain largely rhetorical.

(Non-)interference

China’s unwavering commitment to non-interference in the internal affairs of sovereign nations is alluring to African governments. American officials – and human rights groups – have decried the non-interference policy as a direct challenge to the development of open, democratic governments in Africa. Chinese officials castigate western

hypocrisy and point to flourishing relationships with South Africa, Ghana, Zambia and Kenya as proof that they prioritise political equality with all nations, not authoritarianism. CPC delegations visiting Africa routinely meet representatives of opposition parties, demonstrating the emergence of a distinction between neutrality and non-interference.

The difficulty for China of practising non-interference in “fragile” African states is exemplified in Sudan. In January 2012, 29 Chinese road construction workers were kidnapped by Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-North rebels in an attempt to force China to persuade the Sudanese government to end its military offensive in South Kordofan. As economic interests have multiplied, official policy has undergone subtle reinterpretation. The appointment of an official advisor on Darfur, and flexible mediation in protracted disputes between Sudan and South Sudan, is tacit acknowledgement that China cannot promote its economic ambitions without adopting a more prominent diplomatic role.

The Chinese government’s conduct in Chad is a clear example of melding political and economic interests. Chinese investment in ventures like the US$1 billion Rônier project, a 311km pipeline connecting oil fields in southern Chad to a refinery north of the capital N’Djamena, has buttressed the regime of President Idriss Déby – purportedly in the interests of domestic stability and “good neighbourliness” between Sudan and Chad.12 “We should promote peace and stability in Africa and create a secure environment for Africa’s development”, declared Hu Jintao, China’s president, at FOCAC V.

Chinese officials insist that the policy of non-interference is motivated by a principled objection to unilateral and externally imposed solutions, not ambivalence towards human suffering. In 2012, Chinese personnel were included in six out of seven United Nations peacekeeping missions in Africa. Since December 2008, Chinese warships have participated extensively in joint “anti-piracy” escort duties off the Horn of Africa. The foundations of new policy may be taking shape. Participation in multilateral initiatives provides room for manoeuvre. The need to protect Chinese investment will render the definition of non-interference increasingly ambiguous.

Negotiation and integration

A marked imbalance of power inevitably characterises Sino-African relations, as it does US-Africa and Europe-Africa relations. Despite China’s emphasis on mutual respect and equality of interest in all negotiations, smaller African economies in particular have scant bargaining power. African states are typically reactive – and often uncritical –

in their dealings with China, in all its guises. FOCAC conferences are staged around Chinese pledges. Only South Africa and Ethiopia methodically monitor commitments made by China at FOCAC and other similar meetings (13).

Increased regional collaboration – collective bargaining – would strengthen the hand of African governments. The merits of regional approaches have been acknowledged – in China, and Africa. In 2011, the East African Community signed an agreement with the Chinese government to foster economic, trade, investment and technical co-operation. At FOCAC V, Chen Deming, China’s commerce minister, outlined new measures to negotiate infrastructure projects directly

with Africa’s regional institutions. Regional public goods – the provision of cross-border infrastructure, power, water and health care – are essential for a continent with so many small and landlocked countries. But efforts to promote intra-African trade and integration are frustrated by the continued preference of China – and other trade partners – for bilateral relations.

Expectations for economic returns from natural resource extraction are rising in Africa. In negotiations with Tullow Oil, Total and China National Offshore Oil Corporation, the Ugandan government insisted that the consortium should develop a c.US$1.5 billion national oil refinery to satisfy domestic demand and facilitate regional exports. But the opportunities created by competition between Chinese companies and western multinationals – and high commodity prices – are often squandered. Inadequate investment and regulatory codes, and poor negotiation, frequently stymie pursuit of national goals.

Assertions that Africa needs a “China plan” overlook a more pressing imperative. National and regional strategies that better utilise and deploy the benefits from rising foreign investment – whether from China or elsewhere – are urgently needed. Economic diversification, job creation and poverty reduction are central to all African national development plans. In the 2000s, African governments failed to capitalise on growth fuelled by demand for oil and hard commodities. In most countries efforts to diversify economies were half-hearted. The onus is on African governments to ensure the long-term effectiveness of foreign investment by channelling resources into priority sectors, and to secure terms which enhance skills and technology transfer.

Many African economies have experienced the dire effects on exports of plummeting soft commodity prices. All remain extremely vulnerable to external shocks. The impact on Africa of China’s domestic policy and accession to the World Trade Organization has been immense. While oil and hard commodity prices are unlikely to collapse in the foreseeable future, slower growth in China will certainly be felt in Africa.

An increased focus on stimulating domestic consumption in China will generate uncertainty in many African economies. African governments should be mindful that “South-South solidarity” is rhetorical. In reality, national self-interest is paramount in economic relations. The responsibility for converting trade and investment from China – and other rapidly developing nations – into more diversified economies and sustainable growth rests squarely with African policymakers.