On 21 November 2016, around 40-60 Boko Haram members assaulted Darak in Cameroon’s Far North region (Logone et Chari department), killing six soldiers, the leader of the local vigilante committee and 16 fishermen. They attacked Darak again the following day, and a landmine they planted in Zamga (Mayo Tsanaga department) injured eight troops. The same week, Boko Haram also attempted four suicide bombings that were thwarted in the cities of Kolofata and Mora (Mayo Sava department).

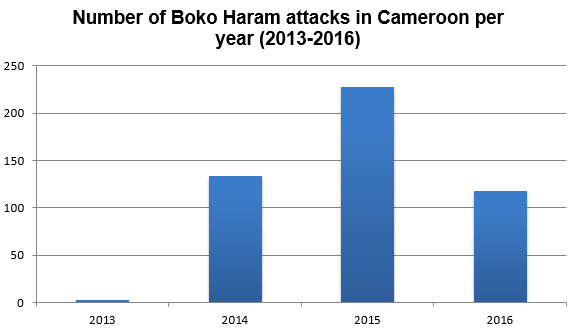

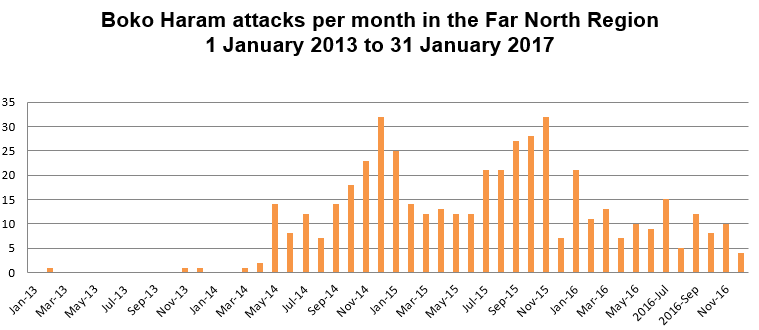

November 2016 was a particularly interesting month for Boko Haram watchers as the attack on Darak, one of the most intense and violent actions of Boko Haram in Cameroon that year, was accompanied by nine other attacks, four suicide bombings and fighting between factions of Boko Haram itself. Seven soldiers lost their lives, the most in any month of 2016. This contrasts somewhat with an overall decline in Boko Haram operations since the start of 2016, as documented in Crisis Group’s latest report on the country and confirmed by a return to lower levels of violence in December and in January 2017. The violence of November does not contradict this broader trend (it was less violent than the same month in 2015 and 2014), but it does serve to remind us that Boko Haram has been able to adapt to the regional security response and is a sustained and evolving menace.

This article looks both at this longer term trend and at the events of November. Data on attacks (including suicide bombings) and casualties since 2013 were compiled from open sources such as the respected newspaper L’Oeil du Sahel, which has a strong presence in Northern Cameroon. This was cross-checked through interviews with the armed forces, the local population, as well as prominent individuals and administrative authorities of the Far North.[1] Other phenomena, such as Boko Haram’s recruitment, while harder to measure accurately, are analysed to better understand the evolution of the jihadist movement in the country.

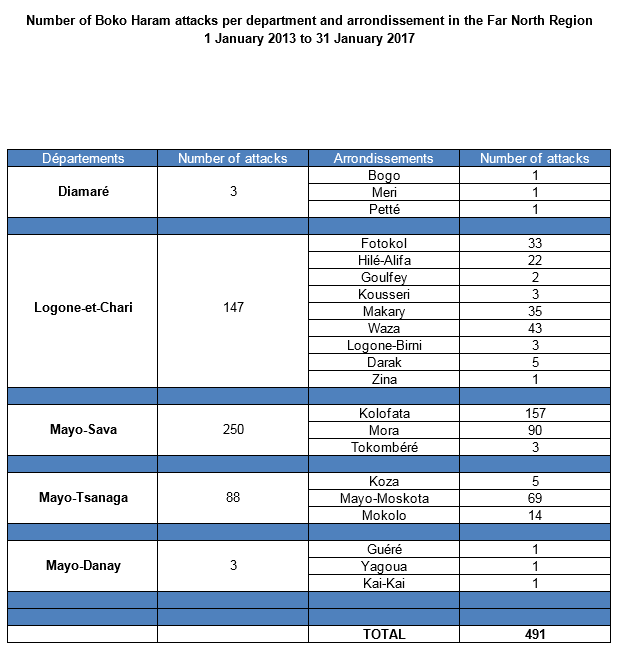

Since 2009, Boko Haram has used the Far North of Cameroon as a transit zone and safe haven: it has set up cells for religious proselytism, logistics, and buying and stocking arms. Apart from assassinating some defectors, the group initially abstained from major violence, as it wanted to avoid any confrontation that would put at risk a vital supply line. The first open operation was the February 2013 kidnapping of the French Moulin-Fournier family. Attacks against armed forces began in March 2014 and the first suicide bombing was in July 2015. Boko Haram has now perpetrated about 490 attacks and kidnappings on Cameroonian soil, and some 50 successful suicide bombings. A further 58 attempted suicide bombings failed.

The jihadist group has kidnapped more than 1,000 individuals in the Far North, including 16 Western and Chinese expatriates, as well as the deputy prime minister’s wife and relatives. According to our estimates at least 1,580 people have been killed since 2014, including 138 military and police.[2] During the same period, the Cameroonian armed forces have claimed to have killed at least 2,100 militants, and the authorities acknowledge around 500 suspected members are in the country’s prisons.

First phase

The intensity and operating methods of Boko Haram’s insurgency in the Far North are evolving, combining conventional and asymmetric warfare. There have been three broad phases: almost completely conventional engagement between May 2014 and June 2015, then a phase of combined conventional and asymmetric conflict until March 2016, after which asymmetric warfare predominated.

In the first phase, Boko Haram frequently attacked the Cameroonian army and important locations: the towns of Kerawa (Mayo Sava department), Balochi and Achigachia (Mayo Tsanaga department) were all temporarily occupied. During these offensives, the group deployed several hundred fighters at a time, armed with assault rifles and rocket launchers, and supported by several armoured vehicles taken from the Nigerian army, and a fleet of machine-gun equipped pickups. In the fiercest fighting, during the second battle for Fotokol from 4 to 6 February 2015, Boko Haram deployed some 1,000 fighters. The clash killed seven Cameroonian soldiers and 17 Chadian troops according to the Cameroonian government. Between 86 and 400 civilians and around 300 Boko Haram members died.[3]

This first phase was the most intense of the conflict. There were an average of 22 incidents per month, of which 16 were attacks. [4] It inflicted the greatest losses on the armed forces: of the 138 military and police deaths in the Boko Haram conflict, at least 89 occurred during this period.[5] It was also the only one in which mass abductions occurred, like the 80 people seized on 18 January 2015 during one attack in Mokolo arrondissement (Mayo Tsanaga department).

Hybrid and asymmetrical warfare

From June 2015, Boko Haram’s capacities noticeably weakened as a result of the loss of supplies and experienced fighters during the first phase. It stopped fighting large-scale battles and rarely deployed more than 100 fighters. Some members resorted to pillaging for livestock and food. Faced with emerging and strengthening local vigilante committees, the group attacked these committees and their communities, leading to an increase in mass murders, burning of villages and suicide bombings. Improvised explosive devices and ambushes were used more frequently, resulting in high civilian casualties: suicide bombings alone have killed 300 and injured around 800 since July 2015. Military casualties reportedly dropped during this phase, although Boko Haram was able to maintain strong pressure against military outposts through small attacks.

Since April 2016, Boko Haram’s shift towards asymmetrical operations has been further accentuated. During this third phase, the number of attacks has declined and most operations deploy fewer than 50 combatants. The monthly average number of suicide bombings, which rose between July 2015 and early 2016, has fallen from 16 to nine. Civilian and military losses have been significantly lower, declining from an estimated monthly average of 61 and six respectively during the first two phases, to 18 and two.

Recruitment into Boko Haram has waned over the last three years and has increasingly become forced. In 2014 the group was reportedly able to recruit as many as 1,000-2,000 people in the Far North, reflecting a belief among some that it would emerge victorious in the conflict, but that year was the high-point. It appears that Boko Haram has lost its allure and is no longer able to attract civilians en masse.

Weakened but not defeated

The violence of November 2016 was a further reminder that while Boko Haram may be weakened, it has not been defeated and is still a serious threat to populations and armed forces. Earlier in the year, the group briefly captured the Nigerien city of Bosso in June and July; the Nigerian military suffered some setbacks in Borno State in June-August; and in Cameroon there were significant attacks against Hilé Alifa,Kerawa and Darak in June and September.

The November activity is partly due to Boko Haram’s split into two factions in June 2016. One group linked to long-time leader Abubakar Shekau operates in the Cameroonian departments of Mayo Tsanaga and Mayo Sava, and has some cells in Logone et Chari and Lake Chad; while that of Shekau’s former number two and now rival, Abu Musa al-Barnawi, son of Boko Haram founder Mohamed Yusuf, is based around Lake Chad and in Logone et Chari. The faction led by al-Barnawi appears less inclined to engage in the pillaging and suicide bombings happening in the Shekau-controlled areas, and is targeting security forces instead (while making deals with them where necessary).

Four further factors explain the increased activity, one that has applied in previous years and the others relevant in the context of 2016. First, from November to May, rivers flowing from Lake Chad dry up, making cross-border incursions easier. Conversely, during the rainy season Boko Haram often rebuilds and resupplies. Since 2014 there have always been more attacks during the dry season, and notably in November, than during the rainy season. In the Far North there were 23 attacks in November 2014, 32 in November 2015 and ten in November 2016, compared to an average of 14 per month since the beginning of the conflict.

Second, according to Cameroonian security forces and local vigilante committees, more intense Nigerian army operations in Borno have pushed Shekau faction combatants to flee to Cameroon, increasing incursions and low intensity attacks. Third, following a significant decrease in attacks from April 2016, and several months without suicide bombings, Cameroonian soldiers started to neglect security. Some stopped wearing helmets and bullet-proof vests, and there were fewer sentries and night patrols – lapses in battle readiness which Boko Haram exploited. According to local traders and security forces interviewed by Crisis Group, the Darak attack on 21 November was partly the result of this less rigorous security stance.

Finally, there have been disputes over the fish trade between Shekau’s and al-Barnawi’s factions. One unit close to al-Barnawi’s faction and led by a Cameroonian has, since at least July, exacted money, rice and fuel from local fishermen and sold dried fish from Niger. A tacit non-aggression pact was said to have existed between them and Cameroonian soldiers, who tolerated fishing and dried fish smuggling in exchange for bribes. The incusion of Shekau’s units into the area shattered this informal arrangement and caught the soldiers off guard, even though they were warned by fishermen of an impending attack in Darak several hours before it occurred. Only the gendarmerie units took the alert seriously and eventually they managed to repel the insurgents of Shekau’s units.

No time to let up

The Darak attack shows the danger of letting up on operations against Boko Haram and allowing the group time to rebuild and resupply. In the Far North, the al-Barnawi faction is still able to recruit, albeit not at previous levels, by combining religion and social issues, as well as by mainly targeting the military. It does not rely on forced recruitment, and often uses material incentives in addition to ideological motivation. According to security forces, deserters from Shekau’s faction have struggled to integrate into al-Barnawi’s group, as he takes time to indoctrinate every new member. Shekau’s faction poses a greater threat to the civilian population. It continues to attack and burn villages, and appears to be behind all the suicide bombings of the last nine months.

Barnawi’s ideological orientation raises fears that its less predatory approach to local communities (at least relative to Shekau’s faction) could enable the faction to improve relations with local communities and even boost recruitment. Meanwhile, Shekau’s faction has suffered heavy losses during the Nigerian-Cameroon operations in the Sambisa forest and in Borno State, but it is not destroyed. Crisis Group sources indicate that members have regrouped in the Gwoza-Mandara hills and Allargano forest.

Boko Haram will probably not regain the conventional warfare capabilities it deployed in Cameroon during 2014, but the ability of both factions to adapt in the past calls for caution. Although weakened, they remain a threat in the region. Cameroonian and regional security forces need to remain vigilant.

Hans De Marie Heungoup is Crisis Group’s Cameroon Analyst. He is grateful to Anais Indriets and Antoine Preel-Dumas for their support in writing this piece.

[1] The data is based on open sources, multiple interviews, and a network of informants. Both civilian and army casualties have been carefully documented by L’Oeil du Sahel, which has a wide network of informants who report incidents by phone or Whatsapp, and whose data has been cross-checked and sometimes adjusted

[2] More than 250 soldiers have also been reported injured since 2014

[3] The Cameroonian government declared 86 civilians were killed during that battle, l’Oeil du Sahel claims to have documented 400, and several inhabitants of Fotokol told Crisis Group hundreds were killed

[4] Crisis Group counts as attacks Boko Haram operations against military posts and bases, massacres, killings, abductions and pillaging of civilian targets. Incidents linked to IEDs and suicide bombings are not included

[5] Based on L’Oeil du Sahel data and Crisis Group interviews with military personnel in Cameroon between 2014 and 2015