April 2011

Sierra Leone is acclaimed as one of Africa’s most successful post-conflict states. But the country remains fragile. Every election since independence has been attended by violence. Support for political parties is polarised on ethnic and regional lines, and underwritten by patronage. Youth unemployment is endemic. Amid early preparations for the 2012 presidential, parliamentary and local council elections, these notes examine the causes of electoral strife, and suggest measures for mitigating future violence.

Green shoots, deep roots

Sierra Leone’s 11 year civil war is infamous for images of child soldiers and amputees, and for the trade in “blood” diamonds. In January 2002, a peace ceremony marked the official end of the conflict. By 2004, 72,000 fighters from various factions were disarmed and demobilised. The international peacekeeping force – whose peak strength of 17,500 made it the largest ever deployed by the United Nations – was withdrawn in 2005.

Sierra Leone’s army, which had effectively ceased to exist in the latter years of the war, was reformed after a recruitment drive. The new force, comprising 8,500 troops, received extensive training from the UK-led International Military Advisory and Training Team (IMATT). The police service has been restructured and retrained. Despite low salaries, discipline in the army and police has improved.

Also Read: Comparing elections in Sierra Leone and Ghana

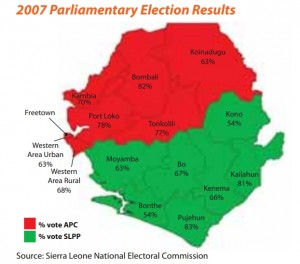

Successive post-war presidential and parliamentary elections have been won by different parties. In 2002, Ahmad Tejan Kabbah and the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) were the victors. In 2007, Ernest Bai Koroma and the All People’s Congress (APC) carried the vote. Both elections were declared free, fair and credible by international observers. Neither result was seriously contested by the defeated party.

President Koroma – formerly the managing director of an insurance company – has impressed international donors with bold declarations to “run Sierra Leone as a business concern”, combat corruption and reduce dependence on foreign aid. New laws and regulations, including a more transparent tax code, have been framed to attract private investment. According to financier and philanthropist George Soros, Sierra Leone has “the genuine potential to become a leading African economy” (1).

Commercial agriculture, infrastructure, health and education are pillars of an ambitious “Agenda for Change” launched by President Koroma in 2008. Funding for agriculture increased from 1.7% of the government’s budget in 2007 to 10% in 2010 (2). Free health care for pregnant women, nursing mothers, and children under five was introduced in April 2010. Provincial roads have been rebuilt. A US$92m investment in Bumbuna Hydroelectric Dam, a project initiated in 1970, has created a facility capable of generating 50 megawatts of electricity.

Sierra Leone remains beset by privation which predates the war. Two-thirds of the population subsists on less than US$1.25 per day. Almost half the population is malnourished. Maternal and infant mortality rates are among the highest in the world, and average life expectancy is 48 years. Youth unemployment is entrenched. While Sierra Leone’ s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is forecast to expand by an annual average of 4.7% in 2008-12,3 a sustained growth rate of 10% is required to combat unemployment and poverty effectively (4).

Corruption is rife in Sierra Leone. A 2006 review by the UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) accused the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) of failing to meet its objectives, and recommended a curtailment of funding for the organisation (5). President Koroma’s government has sought to restore a measure of confidence. The 2008 Anti-Corruption Act sanctioned the ACC to prosecute without prior approval from the attorney-general. By 2011, 11 convictions had ensued, including that of a minister within President Koroma’s inner circle.

Election violence, and accountability

Sierra Leone has held 11 parliamentary and five presidential elections since independence in 1961 (*). All have been accompanied by violence. In the 1967 elections, the ruling SLPP used new public order legislation and rarray boys– thugs – to stymie opposition. A premature announcement by the SLPP-appointed election commissioner that incumbent Prime Minister Albert Margai had won the ballot triggered nationwide riots. A retraction of the announcement in favour of Siaka Stevens and the APC was followed by a coup d’etat. Stevens was reinstated after a counter-coup at the end of 1968.

The 1973 election was boycotted by the SLPP, amid allegations that APC supporters were preventing its candidates from entering nomination centres. SLPP candidates were reportedly kidnapped. In 1977, voting took place under a state of emergency. The APC employed its youth wing and the Internal Security Unit – commonly referred to as “I Shoot U” – to harass SLPP politicians and supporters. In eight constituencies, polls could not be held. In 1982, more than 50 people were killed in an election conducted in a one party state.

“Years of bad governance, endemic corruption and the denial of basic human rights created deplorable conditions that make conflict inevitable” Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission

The 2007 presidential and parliamentary elections were a test of Sierra Leone’s stability. The campaigns became so violent that President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah threatened to suspend the vote and impose a state of emergency. Dozens were injured in clashes in Freetown and in Kono, a major swing district. The SLPP presidential candidate, Solomon Berewa, accused opposition supporters of intimidating his voters. Reports of an assassination attempt on Ernest Koroma, the APC’s candidate, caused riots and the abandonment of his campaign in the south-east.

Perpetrators of violence act without fear of prosecution. While some are party loyalists, others are “hired hands”. The failure to prosecute those responsible exacerbates a lack of respect for the rule of law. It underpins a popular perception that the use of violence is an acceptable – even legitimate – means of securing power.

Misshapen identities

In post-independence Sierra Leone, political loyalties polarised along ethnic and regional lines. The largest ethnic groups, the Mende and Temne, each comprise about 30% of Sierra Leone’s population. The Mende and other smaller tribes in the south and east have traditionally supported the SLPP. The APC is favoured by the Temne, Limba and other tribes in the north, and the Krio community in the west.

Also Read: Diehards and democracy: Elites, inequality and institutions in African elections

Electoral loyalties have not been determined by long-standing ethnic enmity. Beyond the realm of politics, friendships and marriages between ethnic groups are common. But the espousal of particular ethnic and regional groups by candidates for national leadership is ingrained. Ethnic and regional identities have been a convenient – and effective – means of mobilising support during elections.

Within voting blocs, loyalties are not immutable. In the 2002 elections, the SLPP made inroads in the north – traditionally an APC stronghold. As the incumbent government, the SLPP garnered some credit for its role in ending the civil war. The gains were reversed in 2007, when both parties performed badly outside their traditional power bases.

The emergence of a third major political party added dynamism to the 2007 elections. The People’s Movement for Democratic Change (PMDC) was formed by Charles Margai, nephew of Sierra Leone’s first prime minister and son of the second, after his defeat by Solomon Berewa in the SLPP leadership contest. The new party secured a competitive advantage by capitalising on discontent with the indictment of Samuel Hinga Norman by the Special Court for Sierra Leone, the UN-backed tribunal established to try those accused of being most responsible for atrocities committed during the civil war.

The PMDC attracted strong support from the Kamajors, who had formed the backbone of a Mende militia led by Norman and regarded his indictment as a betrayal by the SLPP. The defection of the Kamajors effectively split the Mende vote. In Freetown and the Western Area, where the SLPP had won more than half the seats in the previous election, the APC captured all 21 seats in 2007. The SLPP accused the PMDC of handing victory to Ernest Koroma and the APC.

Patronage and the public purse

Loyalty to political parties in Sierra Leone is sustained by – and sustains – entrenched patronage networks, and corruption. Politicians routinely use office, and state resources, to reward party faithful. Supporters – civilian or military – are provided with money, jobs and services.

In the decade after independence, Sierra Leone’s premiers sought to consolidate power through preferential appointments. Albert Margai, prime minister from 1964-67 and leader of the SLPP, filled the senior ranks of the army, civil service and judiciary with his supporters – regardless of experience or merit. His cabinet was almost exclusively Mende. Under Siaka Stevens, head of state from 1968-85 and founder of the APC, the process was intensified in favour of supporters from the north.

The use of public funds to secure and reward political loyalty undermined state institutions. Hospitals and schools fell into disrepair. Salaries of junior civil servants often went unpaid. Teachers and nurses demanded illegal payments to supplement their salaries. Those unable to pay were denied access to education and health services. By 1985, when Stevens was succeeded by General Joseph Momoh, the Sierra Leonean state existed only in name.

Also Read: Tanzania and Senegal: Inside the Machine

Local paramount chiefs have reinforced political divisions. In the 1960s, Albert Margai granted chiefs the right to allow – or ban – political meetings. Anyone deemed to have misused this authority was deposed or exiled. Siaka Stevens instructed chiefs not to allow SLPP candidates to campaign in their territories, and to order their people to vote for the APC. In 2007, the Office of National Security reported cases of chiefs seeking to disrupt or curtail campaigning.

Entrenched electoral loyalties and corruption have created a commonly-held belief that elections are ‘winner takes all’ contests. Voters presume that the SLPP will reward the south and east, and the APC will favour the north and west. Defeat at the ballot box will entail exclusion and disadvantage for an electoral term.

Youth, and muscle

Youth groups have become a more potent force in Sierra Leone’s elections than ethnicity or regionalism. The young have been most disadvantaged by endemic corruption, and have suffered most from the disintegration of state services. In the 1980s, Sierra Leone’s literacy rate was just 15% (7). Education suffered further as schools closed during the civil war. Many young men and women joined the various factions – some voluntarily, but many by force.

“The youth problem has become chronic”. President Ernest Bai Koroma (8)

Sierra Leone is beset by a burgeoning generation which has received no formal education and possesses few skills. An estimated 800,000 young people, about 14% of the population, are unemployed or work for no remuneration (9). Those who have jobs are often exploited, enduring abject conditions for negligible pay. A 2010 UN Security Council briefing noted that a growing number of young men are “idle, concentrated in urban areas and frustrated by social marginalisation” (10). Unemployed young men are susceptible to manipulation and exploitation.

Also Read: The more things change… 2012 elections in Sierra Leone

In the 2007 election campaigns, political parties employed high profile ex-combatants from various rebel groups. Ernest Koroma hired Idrissa Kamara, a former Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) commander known as Leatherboot, and mid-ranking former Revolutionary United Front (RUF) fighters to join his personal security unit. Solomon Berewa engaged Hassan Bangura, or Bomblast, also a former AFRC commander who became second-in-command of the West Side Boys. The PMDC was backed by the Kamajors. These alliances were designed to gain political clout, but youth groups – and unemployed young men in particular – were responsible for most of the violence during the 2007 campaigns.

Party “task forces”, established to handle security and protect party property, are a feature of elections in Sierra Leone. Young men are brought into the party youth wings – for token payments or promises of future benefits – to intimidate voters and break up opposition rallies. Their loyalty is not guaranteed. Many hold membership cards of more than one party, and switch allegiances for greater reward. There is profound distrust between politicians and marginalised youth. With few opportunities for betterment, the young pose an escalating threat to post-war stability.

Twenty twelve

The 2012 presidential, parliamentary and local government elections will be won by the APC or the SLPP. The PMDC’s popularity has waned since 2008, and the SLPP appear to have regained the support of the Kamajors. In September 2010, a UN Security Council resolution stressed the “potential for an increase in tensions during the preparations for and the period leading up to the 2012 elections … due to political, security, socio-economic and humanitarian challenges” (11).

Predictions of electoral violence are well-founded. In March 2009, the SLPP headquarters was attacked after five days of clashes between supporters of the two main parties in Freetown, Kenema, Gendema and Pujehun District. A joint communiqué condemning the fighting was issued by all parties, but violent confrontations occurred during other by-elections in 2010. Rumours of negotiations between prominent ex-combatants and the APC and SLPP abound.

A December 2010 local council by-election in Kono was preceded by “incidents of political violence and intolerance” (12). The SLPP office in Koidu City, and buildings associated with APC officials, were vandalised. Senior SLPP officials, including two presidential candidates and the deputy minority leader of parliament, sustained injuries in attacks allegedly carried out by APC supporters. SLPP MPs boycotted parliamentary proceedings in protest.

Distrust between the APC and the SLPP is intense. In December 2010, two SLPP members were given ministerial positions in a cabinet reshuffle. Both appointees were promptly suspended from the SLPP.

Recommendations

In the run-up to Sierra Leone’s 2012 elections:

The joint communiqué signed in April 2009 must be fully implemented. All political parties agreed to co-operate “in preventing all forms of political incitement, provocation and intimidation” that might encourage violence. No one has ever been prosecuted for violent conduct during elections. Donors should exert pressure on the government to ensure that all outbreaks of violence are investigated, and the perpetrators prosecuted. Those who recruit malefactors and those who incite violence should be deemed equally responsible.

The effective and impartial conduct of state institutions will be a prerequisite for free, fair and peaceful polls. Sierra Leone’s National Electoral Commission, Political Parties Registration Commission, Office of National Security, police and electoral offences courts, jointly have the authority to prevent an escalation of illegal and violent behaviour. These institutions must be unequivocally supported by political parties and donors. The UN Secretary-General’s Executive Representative in Sierra Leone has called on the National Electoral Commission to “show greater flexibility in discussing electoral concerns” (13) with all parties, in order to deflect any accusation of bias.

Political parties should demonstrate real support for efforts by the newly-formed All Political Parties Youth Association and All Political Parties Women’s Association to promote peaceful elections. The government should emphasise the legal obligations of paramount chiefs before and during the elections – and the penalties for breaches.

The APC and SLPP have relinquished control of party radio stations. The new, independent Sierra Leone Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC) should act as a forum for all political parties to debate electoral issues. Radio is a powerful medium in a country with one of the lowest literacy rates in the world. Debates and impartial election coverage by the SLBC can help to inform voters, and encourage voting determined by issues and performance.

Recent prosecutions by the Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) have been welcomed, in Sierra Leone and abroad. Further prosecutions would help to counter the widespread belief that politicians are not accountable for the use, or misuse, of public funds. The ACC needs to investigate more closely how corruption is used to secure political loyalty.

In the medium term:

Party ‘task forces’ should be disbanded, and outlawed. Special police units should assume responsibility for the protection of political candidates and party property.

Political parties and individual candidates should be required by law to disclose all donations, and account for the use of funds. A limit on donations should be agreed by all parties, after consultation with civil society groups and donors.

Infrastructure and other development projects funded by international donors need to benefit all regions. Increasing government revenues from natural resource extraction must also be deployed in a demonstrably equitable manner. Disbursement of national income and donor funds for the benefit of government and opposition supporters alike will help to counter political divisionism, and the public perception that elections are a “winner takes all” contest.

Enduring peace and stability in Sierra Leone is dependent on a substantial expansion of educational and employment opportunities. In 2010, the World Bank announced a three year US$20 million to develop the practical skills of 18,000 unemployed young people. An additional 30,000 will be employed in public schemes to rehabilitate infrastructure. A new Ministry for Youth Employment and Sport was created in 2010. Much more is needed. Agriculture and agribusiness offer good opportunities for large-scale employment. The development of labour-intensive commercial agriculture in Sierra Leone should be a priority for donors and government.