“A 50kg bag of rice cost 90,000 Leones in April, it now costs 140,000 Leones” Abdul Bundu Conteh, resident of Freetown

Inflated food prices without reciprocal wage increases and possible job losses as a result of Ebola are increasing the strain on many Sierra Leoneans. Mohammed, the security guard who works in my compound in Freetown, earns around 250,000 Leones (around US$54) per month. He has seen price increases of over 50%, further squeezing his already tight budget and making life “too tough”. With the virus showing no signs of abating, the scale of these hardships is only likely to rise and affect more Sierra Leoneans.

A drop in GDP growth projections from 11.3% to 8% between June and September 2014 is significant, but cannot be solely ascribed to Ebola: mining has been hard hit by the plummeting global price of iron ore, the country’s primary extractives export. Such figures are abstract and meaningless for most Sierra Leoneans, the majority of whom work in the informal economy. Since 2012, the country has experienced double digit GDP growth, but 60% of people still live below the national poverty line.

For farmers, rural dwellers, and informal urban workers, subsistence and survival are the main economic concerns. With the continued spread of Ebola, a harsh existence is becoming even harsher.

Life on the Fringes

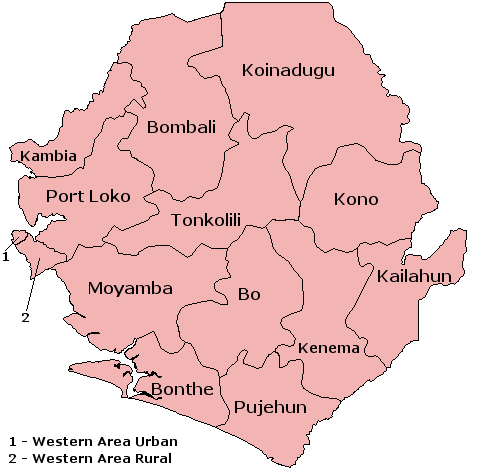

September signals the end of the rains in Sierra Leone and the start of harvest season for both staple food crops like rice, and cash crops including cocoa. But a recent rapid food security assessment by the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) found that 47% of respondents said Ebola was considerably disrupting their farming activities. In Kailahun District, in the far east of the country where the outbreak was first identified, many crops have been left in the ground due to farmers’ unwillingness to work collectively to harvest, as they would normally. Even in Koinadugu District, the region least affected by the virus, farmers have found it difficult to get vegetable produce to markets. This has resulted in a large part of the harvest being left to rot or sold at throw-away prices.

For cash crops such as cocoa, which has almost no internal market, farmers have suffered due to border closures, airlines cancelling scheduled flights and what Donald Kaberuka, President of African Development Bank, has described as a ‘pandemic of fear’, which has scared off international buyers.

The effects are not only limited to agricultural production. In urban centres such as Freetown, taxi and okada (motorbike taxi) drivers have been significantly affected by the outbreak. Not only do they face the potential risk of carrying Ebola patients, they must contend with the government restricting working hours to between 7am and 7pm, and reducing the number of passengers who can travel in taxis from 4 to 3.

With the cost of hiring vehicles from owners remaining constant – at best – already slim profits are being further constricted. In response, drivers are increasing prices, passing the economic cost of Ebola on to passengers. Although fuel prices are constant as a result of subsidies, the cost of longer journeys has doubled to ensure their viability. Furthermore, the government’s initiative to set up checkpoints across the country in an effort to control the outbreak has introduced an additional financial burden. According to Foday Conteh, a taxi driver I use often, who frequently travels between Freetown and Makeni, the checkpoints “are places where the police make you pay to pass”.

Short-Term Improvements

To improve the immediate economic situation, there is a need to prop up both the formal and informal markets. This will not be easy, but a starting point would be to use Sierra Leonean labour and local materials to build Ebola treatment centres which should in turn be mandated to purchase supplies from local markets, whenever possible. Yvonne Aki-Sawyerr, a prominent Sierra Leonean businesswoman, believes that this can best be done by encouraging “maximised use of local supplies when DFID or UN award contracts, to support small and medium enterprises that have been devastated by the downturn”.

The government and development partners must recognise the importance of supporting the informal economy if they are serious about a sustainable intervention. If not, the foundations of an economic crisis to follow the Ebola outbreak will have been laid.

by Jamie Hitchen, Policy Researcher, Africa Research Institute

Home page image: Mark Condren for GOAL Ireland 17.9.2014