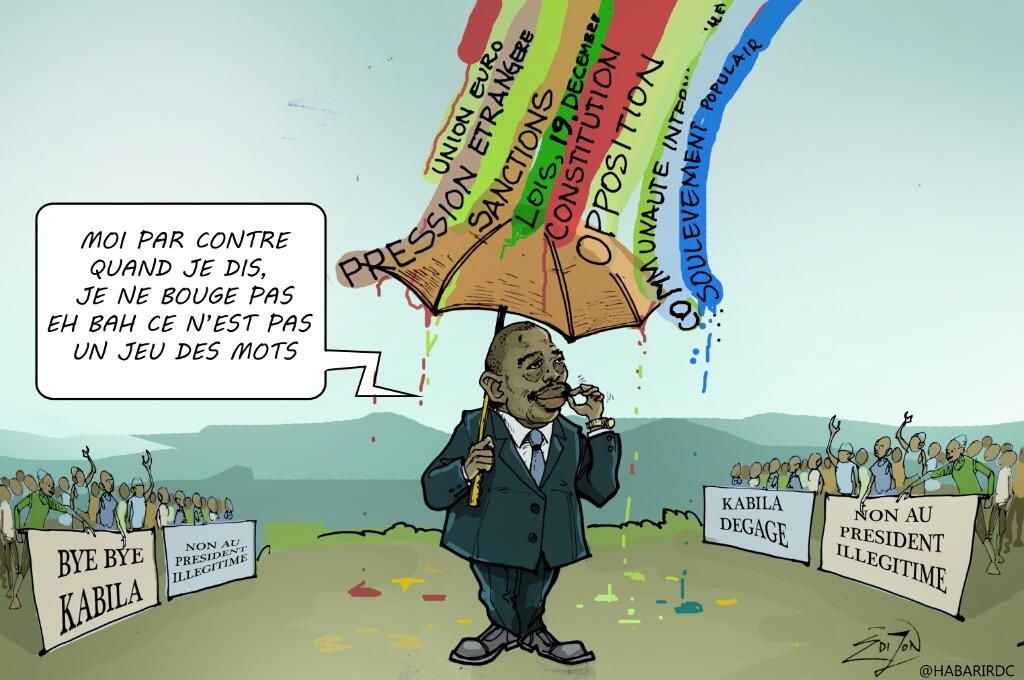

National elections are scheduled for 23 December 2018 in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It is likely that Joseph Kabila, who has managed to delay polls since his mandate ended in 2016, will continue to do so. He will buy time until he can find a pretext to remove constitutional term limits that prevent him from standing for re-election.

Joseph Kabila came to power in 2001 after the assassination of his father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila. In 2015, he failed to push through a draft law enabling him to extend his rule to a third term due to widespread opposition. Instead the St Sylvestre Accord, a political compromise brokered by the National Episcopal Conference of the Congo (CENCO) bishops, allowed him to stay in power one year beyond the end of his legal term on 19 December 2016. This was conditional on holding free and fair elections by the end of 2017 at the latest, and that Kabila abide by the constitution and step down following the elections.

Budget and logistical constraints were used as a reason to avoid organising elections, and Kabila declared he would stay until December 2018 to ensure voter registration was completed. As a result, the country was plunged into a new political crisis. Between January 2015 and December 2017, violence intensified as mass anti-government protests demanded Kabila’s resignation. The security forces responded harshly, and violent repression of political demonstrations continues.

On 5 November 2017, the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) published an electoral calendar suggesting that the long overdue presidential, legislative and provincial polls would take place on 23 December 2018. The announcement was welcomed by the international community as a significant step towards achieving a first peaceful, democratic transfer of power in DRC. However, Kabila will use various strategies to stay in power.

- No united internal threat

Political opposition to Kabila is extremely weak and deeply divided. The assets of key opposition activists have been frozen and influential leaders remain either in prison or in exile. Kabila has successfully quashed his three major challengers. The Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS), lays claim to being the most popular political party. Its leader, Etienne Tshisekedi, finished second in the controversial 2011 election, securing 32% of the vote to Kabila’s 49%. But when he died in February 2017 he was succeeded by his son, Felix, who displays neither the charisma nor the experience to challenge Kabila and is referred to as a “lion cub with no teeth”. In a recent poll Moïse Katumbi was named as the most popular opposition figure. But the former governor of Katanga province remains in exile, in effect excluded from running and facing an investigation into several alleged “crimes” including holding Italian nationality.

Finally, the Catholic Church has been disempowered It has always played a significant role in mediating and influencing political outcomes and peace agreements in the DRC and, during the most recent crisis, looked likely to play a leading part in efforts to oust Kabila. However, the response of police and security forces to mass demonstrations including church followers has been so severe that the Church has been discouraged from openly backing the opposition movement. Due to its popularity and status, the Church could instigate action that would trigger violence on a much larger scale, possibly with the potential to escalate to a crisis akin to the 1994 Rwandan genocide. However, Kabila knows that the leadership is decentralised, not cohesive and reluctant to apply further pressure. The biggest threat to him from this quarter, mainly in Kinshasa, remains manageable.

The alliance of political parties that has backed Kabila is also deeply divided. Each is only loyal to him because their members gain the rewards of being part of his government. The most influential individuals are waiting for the president to nominate his successor. He is unlikely to do so, and will hold off announcing his intention to run for a third term as long as possible, ensuring there is no time for a serious challenge to develop within his own camp.

2. Continuing conflict

The FARDC – the military – is no threat to Kabila as it is run as a private and personal security operation, is extremely weak and corrupt, and has badly trained and poorly paid personnel. Kabila has maintained control through his most trusted and loyal officers, who are rewarded with prestigious and lucrative positions to manage local threats in the regions. The FARDC has been totally dysfunctional as a national force since it was formed at the end of the Second Congo War, in July 2003, through the Inter-Congolese Dialogue and Global and Inclusive Agreement signed in South Africa. This “brought together” the national armed forces and several rebel groups, including the Rwandan-backed RCD-Goma, the Ugandan-backed MLC of Jean-Pierre Bemba and RCD-Kinsangani, and various Mai-Mai ethno-nationalist militias.

The presence of what remains the world’s largest – and most expensive – international peacebuilding/ peacekeeping intervention, the United Nations Organization Stabilisation Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO), is also no hindrance to Kabila. The mission is regarded as being ineffective and inefficient by most observers. There is even a possibility that Kabila could deliberately push Western powers to back a new military offensive from the east – supported by Uganda, Angola and Rwanda – to forcibly remove him from power. In the event of such a war, MONUSCO would act as a peacemaker rather than peacekeeper and, with the support of the UN Forces Integration Brigade (UNFIB), would actively endeavour to limit the extent of any incursions. This would inevitably lead to a political dialogue to ensure a “peaceful” transition (and provide guarantees to Western and multinational business interests through negotiations). In DRC, peace agreements and accords tend to be stronger than the constitutional law.

A major military incursion would enable Kabila to declare that the country was too unstable to organise free, fair and credible elections. He has used similar tactics regionally, allowing and actively maintaining conflict across the DRC, especially in Tanganyika, Kasai and Kivu. More than 13 million people are already in need of emergency humanitarian assistance, and about 4.5 million are internally displaced. In the northeast, more than 50,000 families have recently fled to Uganda, thousands remain trapped in the Lwenzoli forest, and over 650,000 refugees have fled from Tanganyika province to Tanzania. There are around 120 armed groups in the region, attacks are ongoing especially in South Kivu, and people continue to flee, in fear for their lives. The electoral law stipulates that if a quarter of the country’s landmass is affected by instability, national elections can be postponed

- Technical difficulties

In February 2018, the Electoral Commission (CENI) introduced new electronic voting technology imported from South Korea. The system was described as being efficient, cost-reducing and effective at limiting electoral fraud, but it failed during a demonstration in front of a parliamentary commission and has, following further controversy, been rejected by both civil society and opposition groups. There have been allegations regarding the relationship between the CENI and a bank linked to the president’s family. Kabila and the CENI will argue that the election cannot go ahead without the new voting machines. Similarly, while voter registration in DRC was completed in February 2018, there are still more than 10 million Congolese in the diaspora who have not been able to register. Arranging for the diaspora to register is another potential pretext for delay.

- Friends and neighbours

Leaders in DRC tend to be regionally “manufactured”. Four of Kabila’s major regional allies have left the political scene in just two years: the former presidents of Angola, Tanzania, South Africa and Zimbabwe. During their presidencies, the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) became significantly involved in DRC, expanding its influence following the defeat of the M23 rebels by the UNFIB, a force led by Tanzania and South Africa. José Eduardo dos Santos, Jacob Zuma and Robert Mugabe had financial interests in DRC; Jakaya Kikwete’s main motivation was a determination to prevent any increase in Rwandan influence in eastern DRC. With support from SADC member states, Kabila was able to isolate both Rwanda and Uganda – both hostile to him for not resolving the persistent conflicts in eastern DRC – and deter them from interfering militarily.

New SADC leaders have different priorities: Cyril Ramaphosa (South Africa) and Emmerson Mnangagwa (Zimbabwe) have elections in their own countries and are keen to demonstrate their democratic credentials. Kabila’s main political opponent, Moïse Katumbi, has been allowed to hold rallies in South Africa. The focus for the president of Tanzania, John Magufuli, is very different to that of his predecessor, Kikwete: he is more concerned with internal priorities and regional economic development. On the face of it, the only good news for Kabila among the changing faces within SADC is that Ian Khama, who had clearly demanded that Kabila allow a democratic process in DRC and was a vocal and influential figure in SADC, has been succeeded as president of Botswana by the inexperienced Mokgweetsi Masisi. Kabila knows that other regional leaders have extended their rule beyond the legal limit and SADC’s ongoing commitment to UNFIB is a foil to threats from DRC’s neighbours in the east who would prefer to see him removed from power.

- Further violation of the constitution

Kabila is not concerned about accusations of violating the constitution because it is already desecrated. He heads illegitimate institutions and a corruptible leadership system based on political patronage. Technically, Kabila is not the only one who has overstayed in power. Like Kabila, members of the lower parliament chamber were elected in 2011; members of the upper parliamentary chamber, the Senate, and the provincial parliament were elected in 2006. None have ever alluded to their illegitimate status, still less resigned.

In such a climate of illegitimacy, Kabila will use the “Burundi system”, by which he argues that “legally” his second mandate was his first and therefore he can stand in the next elections. Kabila may try to prepare national and international opinion for this gambit by arguing that the constitutional revision in 2011 violated some aspects of Article 71, which modified and, in effect, interrupted his presidential term.

- Playing off international interests

DRC has always been of global “strategic” interest due to its size, location and vast mineral wealth. With such significance, Kabila is acutely aware that no leader can survive unless they satisfy Western governments and multinational and Chinese commercial interests. Kabila has successfully managed a brokerage strategy to date, and accumulated huge wealth as a result. While he is currently regarded by many of them as a liability, multinationals do not as yet have any alternative guarantor of their interests in DRC.

As for Western governments, their agendas differ. Belgium, using its EU “role” as former colonial power and self-appointed expert on DRC, seems to be pushing hard for Kabila to leave power. But its wishes cannot be fulfilled unless endorsed by France – and Kabila has opened doors for French multinationals. If he also maintains his enmity with Rwanda, he will remain friends with France, to his own benefit. In the US, DRC is still very low on Trump’s foreign policy agenda and his commitment to promoting democracy abroad remains unclear. The Trump administration will most likely be driven by security and economic priorities which Kabila will endeavour not to subvert.

Given that the political and military crises that have repeatedly enabled Kabila to avoid elections show no sign of abating, and that he has several means at his disposal to ensure they are delayed again, the president looks set to extend his rule beyond 2018. In this scenario, decisive action from Western governments in the event of a further postponement of the elections is unlikely.

Alex Ntung is an author, a PhD research candidate, a professional member of the UK Expert Witness Institute and a DRC political and security analyst. Twitter: @AlexMvuka

Featured image: ‘President Kabila casts his vote during Presidential and Legislative elections in Kinshasa’ MONUSCO/John Bopengo (Creative Commons).