Nurse Belkisu survived the virus and now works on the Ebola ward at Connaught; King’s Sierra Leone Partnership

“The Ebola virus has divided families, societies and has created boundaries within the country. Certain regions within the country have been quarantined….the social, economic and cultural impact this has is immense.” – Reverend George Buannie, in conversation with the author, September 2014

The Government of Sierra Leone’s official figures for 29 October 2014 record 786 survivors of Ebola. As the death toll rises, so does the number of survivors – a group that is quickly becoming ostracised. This post reflects on the stigma that has accompanied the virus at the individual, national and international level.

Individual

Ebola survivors, health workers and family members of victims all suffer from related stigma. Re-integrating the mounting numbers of Ebola orphans into family structures is proving difficult. Fear, is the major problem, caused in the main by poor public health communications from government officials and misinformation spread by rumours within communities. The fear is causing individuals to stay at home, rather than report for testing at the limited number of medical facilities which remain open and staffed, thereby undermining efforts to treat patients. Early intervention is important for improved outcomes. When people avoid hospitals, prevention also becomes more difficult as the infected put their family members at risk.

Addressing stigma should be an indispensable component of the response to Ebola. Lessons can be learned from stigma reduction strategies that were developed in response to HIV/AIDS. The dissemination of messages which communicate the key features of the virus to at-risk communities in order to improve their understanding of transmission and symptoms could play an important role in neutralising the impact of fear. Traditional and religious leaders have a vital role to play in conveying these messages, but communities must also be able to ask questions and share concerns. Their voices have not yet been sufficiently heard, and the absence of a mechanism for sharing concerns risks exacerbating tensions.

National

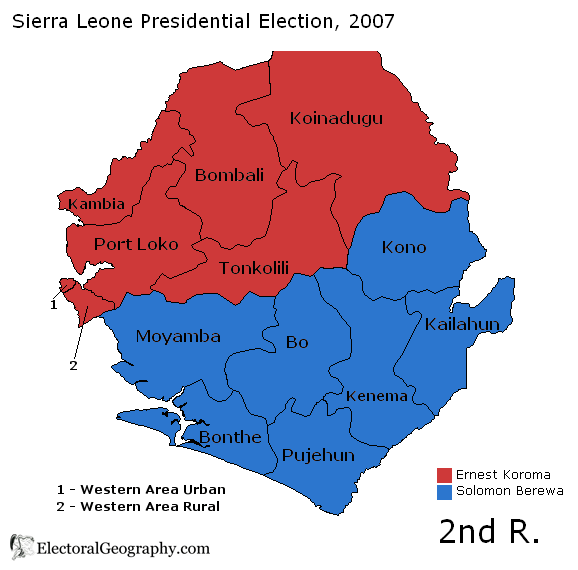

The emergence of the Ebola virus in Kailahun district, in the remote south-east of the country, where civil war began in 1991, provided ammunition to those seeking further evidence of the north-south political divide that has existed in Sierra Leone since independence. President Koroma’s All People’s Congress (APC) has its support base in the country’s northern districts while the opposition Sierra Leone Peoples Party (SLPP) draws its support base from southern districts.

An underlying perception, in some quarters, of a north-south, fractured and politicised response to the crisis has returned in recent weeks. Although numbers of recorded Ebola cases have decreased in Kailahun the main treatment centres were established there, and in neighbouring Kenema. New centres are being established in Freetown as the number of cases increase, but many patients are still being transported to the southern districts for care.

According to a former colleague of mine at VSO, Edward Koroma, this is perceived as “putting the communities at risk by continuing to bring infected patients into the districts and, consequently, fostering local resentment”. For now the country remains united in its fight against the virus, but stigmatising whole districts as “Ebola centres” has negative social, economic and ultimately, political ramifications.

International

The stigma extends beyond national boundaries. Some Sierra Leoneans feel abandoned by other African states that have closed their borders in response to the threat, hampering the relief effort, and are resentful of the African Union – whose officials only visited for the first time on 23 October and left after just a few hours.

Ghanaian President John Mahama reflected on this on his return from a visit to Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. In a speech delivered in the UK, in October, he described how Liberia, Guinea and Sierra Leone feel “isolated and ostracised”.

Africa, as an imagined whole, is being increasingly stigmatised as Ebola cases are treated in Spain and the USA. Further travel bans have been introduced by Canada and Australia, passenger screening is taking place, and examples of UK schools cancelling trips to countries as distant from the outbreak as Tanzania characterises how panic and prejudice have trumped rationality.

The stigma associated with Ebola has many facets, but the result is always the same: isolation and mounting, mutual distrust.

Way Forward

Changing how Ebola survivors are perceived is critical for easing community tensions and effecting the eradication of Ebola. Given that survivors have immunity, once fully recovered they could work at treatment centres in a number of capacities. According to a clinical psychologist currently working in West Africa, who does not wish to be named, they could:

- Encourage and talk to patients

- Advise those who run treatment centres on care and living environments, from a patient’s point of view

- Provide positive reinforcement for highly pressured healthcare workers

At a global level, President Obama’s public hug with Ebola survivor Nina Pham was a deeply symbolic moment in tackling survivor stigma. By contrast, President Koroma avoided physical contact with the survivors he met last month in Hastings. It will be hard to shift community attitudes towards survivors unless senior officials lead by example.

by Jamie Hitchen, Policy Researcher, Africa Research Institute