This article was first published by Sunrise Newspaper and is republished here with the permission of the author

This week, I was invited by the Rotaract Club of Kampala, to talk about interest rates; why they are high and how we can bring them down. I often approach talks of this nature in an unconventional way. I love facts. So I gave the Rotarians a good dose of both current and past realities.

Then we interrogated the main market failures in Uganda’s banking sector as well as my views on the popular current debate: should we go the Kenyan way (capping) or should we not? My views on this are on the shelves, so I won’t consume more space on that.

However, apart from these, I also helped my hosts to put our challenge of high interest rates in the perspective of information economics and the various on-the-ground realities in Uganda. This is where I will keep my pen this week.

Researchers have time and again found — across countries, space and time — that when banks keep interest rates high for a long period the “safe” or creditworthy borrowers are discouraged from borrowing. The result is that they end up lending people with higher risk of defaulting on loans. This is what economists call ‘adverse selection’. Researchers have also found that high interest rates lead ‘good’ borrowers to invest in risker projects, something economists refer to as ‘moral hazard’.

Efforts to reduce costs

These two great findings imply that it should be in the banks’ interest to use lending rates to achieve two things: to attract creditworthy and ‘less risky’ borrowers to apply for their loans and to induce borrowers to undertake safe projects.

I often hear people talk about how “Ugandan borrowers are too risky”. For decades, banks have been claiming that they charge high interest rates to hedge themselves against the risk of borrowers defaulting. They decry poor quality of collateral (encumbered land titles, for example). They have also claimed that Ugandan borrowers lack addresses and that there is limited information about them.

Bank of Uganda (BOU) supports the banks to explain away the high rates by citing the structural factors above plus poor infrastructure (ICT, roads, electricity, and security) which raised the banks’ operational costs; high litigation costs for contract enforcement made loan recovery expensive.

However, in recent years many of these ‘structural factors’ have been improving. Any well-meaning Ugandan agrees that our infrastructure, be it roads, ICT, electricity or security, has tremendously improved since the early 1990s.

With the computerisation of land and company registries, it is also not far-fetched to claim that the collateral quality has improved. Government has also issued Ugandans with national IDs and established a credit reference bureau that provides banks with timely and accurate information to facilitate assessment of borrowers’ risks to reduce default rates.

Principal-agent problem

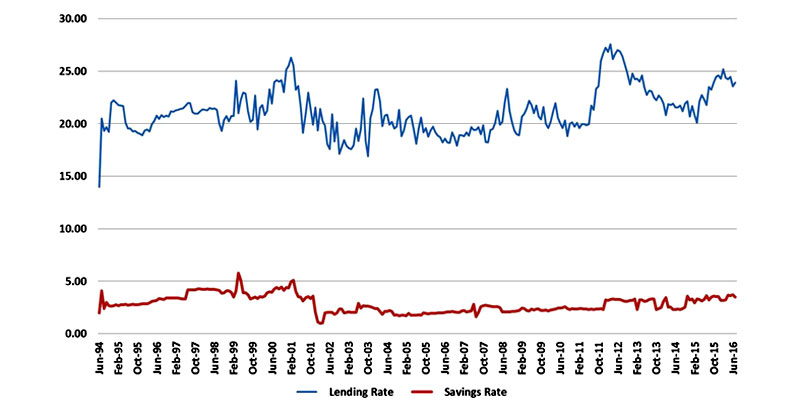

Despite these improvements, however, banks have not reduced interest rates. Above, I have plotted a curve that shows the average lending rates that banks have been charging their borrowers from June 1994 to June 2016.

It also shows that average savings rates that the banks have been offering those who deposit money with them in savings accounts. It is clear from this graph that the two rates have not changed much since we liberalised interest rates 22 years ago.

Banks have in the past two decades continued to pay their savers an average of 3% and charged borrowers (of the same savings) an average of 23%, implying an interest rate spread of nearly 20%. This is simply unexplainable, not even by the ‘reasons’ perennially given by the banks and defended by their regulator, the mighty BOU.

To me there an apparent ‘principal-agent problem’ in Uganda’s banking sector. The problem arises when the agent (a manager) cheats the principal (the owner of an asset) simply because, owing to information problems, the principal has difficulty to monitor what the agent does.

In the case of banks, savers (and owners of equity) are the principals while the banks are the agents. It goes without saying that savers find it difficult to monitor the banks to verify that the banks are not solely furthering their own objectives by disregarding those of their savers.

Savings crisis

I will use a simple example. Suppose, I opened a savings account in bank X and deposited my hard-earned Shs.1 million on October 12, 2015. The bank offered me an interest (profit) of 3% per year. I went back to the bank on Wednesday October 12, 2016 and the bank handed me the Shs.1 million I ‘saved’ with a profit of Shs.30,000.

In the meantime, my sister went to the same bank and borrowed the Shs.1 million I had saved with them. She was asked to pay 25% per year to use it in her small business. So on the same day, as I went to pick my savings, my sister also went back to return the Shs.1 million. The bank charged her Shs.250,000 and picked Shs.30,000 of the Shs.250,000 and handed it to me as my share. That is how the situation has been, and still is, in Uganda.

Actually, I formulated this simple example on the assumption that the inflation rate stayed constant throughout the year. This is rarely the case. Inflation in Uganda is volatile. When it increases, the bank reserves the right to raise the interest that my sister was supposed to pay (for my million shillings), say to Shs. 280,000, but the same bank is under no obligation to increase my own interest from Shs.30,000. If you observe keenly, the lending rate curve in the graph is more volatile than the savings rate curve.

Banks in Uganda are quick to insulate themselves against inflation but are less concerned about their savers. Now tell me, how would you expect a rational person with basic financial knowledge to save in Uganda’s banks?

No wonder Uganda is facing a savings crisis. People simply do not save. The few who are saving, have found other ‘sensible’ ways – constructing apartments and other real estates (dead capital); buying land or cattle (tied capital); or converting their money into dollars which they keep under their mattresses (smart but economically inefficient banking).

Moral hazard

For years I have been writing that banks ought to know better a few generic facts that sustain an economy and by extension the banks themselves. First, a country needs cheap capital to develop. Second, the interest rate a bank charges may itself affect the riskiness of a pool of loans by either sorting potential borrowers (adverse selection) or affecting the actions of borrowers (moral hazard) as we have already seen.

Third, higher collateral requirements (increasing the liability of the borrower if the project fails) lead borrowers to finance smaller projects with higher risk (building apartments and shopping malls, buying trucks to speculate on newly found oil, wedding loans, cars and mortgages), instead of investing in manufacturing, agro-processing, agriculture, and tourism.

Fourth, banks in Uganda are making abnormal profits. In economics abnormal profits is defined as unfair profits often made by monopolies and oligopolies. Competitive firms make ‘normal profits’ or ‘reasonable profits’. Abnormal profits are made by businesses that can set prices above their marginal cost (in the case of a bank the cost they incur to serve one additional client).

Ten years ago, someone raised a similar complaint and the BOU Governor, Emmanuel Tumusiime-Mutebile retorted, “What is wrong with banks making money?” I asked him, “What is wrong with banks making money reasonably?”

Back then, my question sounded rhetorical to Mutebile and many other Ugandans. Today, I am sure Mutebile and many bank managers have realised there was always some sense of reality in my question. Following Kenya’s (unwise?) move to cap interest rates, bankers in Uganda are in a panicky mode. The other day I saw the BOU and bank managers trying to persuade Ugandan MPs not to go the Kenyan way. Banks have finally agreed to follow the base rate (the CBR) set by the BOU.

Incentive to cheat

Yet I am hesitant to blame the banks. There is every incentive in this country by market players to flout the rules of the game and make the money Mutebile wants them to make. Banks know it is damn difficult to cost-effectively monitor them. They are more familiar with the industry. They have more information than their regulator. I have no doubt that BOU gets most of its information about the performance of banks from the banks themselves.

At the same time, it does not require one to be a genius to know that by continuing to pursue maximum profits by colluding to charge high interest rates, banks in Uganda might be bordering the risk their Kenyan counterparts sought. This is what I refer to as an ‘own goal’. Conventionally, banks are advised to identify borrowers who are more likely to repay in order to get a higher expected return. The interest rate which an individual is willing to pay should act as the main screening device to identify “good borrowers”.

Everywhere else, except in Uganda and Africa in general, bankers know that high interest rates increase the average “riskiness” of those who borrow. Secondly they also know that higher interest rates induce firms to undertake projects with lower probabilities of success but higher payoffs when successful.

So my question is simple: Why don’t Ugandan banks reward ‘good’ borrowers by lending to them at lower interest rates, which in turn would induce them to undertake safer projects to create a win-win situation? Is this rocket science?

Ramathan Ggoobi is an Economist and Policy Analyst. He teaches economics at Makerere University Business School, where he heads an economic think-tank — MUBS Economic Forum.