ARI researcher Jamie Hitchen outlines how Pujehun, a relatively poor district in Sierra Leone, succeeded in declaring itself Ebola-free.

Pujehun, in the south-east of Sierra Leone, was the first district in the country to declare itself free of the Ebola virus. On 10 January 2015 it reached 42 days without recording a new Ebola case, the measure used by the World Health Organisation (WHO) to declare a region free of the virus. With 31 confirmed cases, and 24 deaths in total, it was one of the districts least affected by the outbreak.

District government officials are still exercising caution and they are right to do so. Initial claims that the virus had been contained in Guinea did not hold, and with neighbouring districts still reporting cases, this is not the time for complacency. Pujehun District Youth Council (DYC) Chair, Brima Fullah, told me that “a new district strategy to screen all households will start in February, to ensure that the virus has been fully eradicated”. But how did this relatively poor, albeit remote, district do so well in containing and defeating the virus?

Pujehun District Council, under the leadership of Sadiq Sillah, a member of the opposition Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP), acted quickly to put in place emergency measures that the government of Sierra Leone would eventually replicate nationwide: banning social activities, closing markets and restricting worship. Strong local opposition amongst some citizens was overcome by garnering the support of religious leaders and the DYC. According to Sylvia Blyden, a prominent youth activist, local leaders in Pujehun incorporated the youth into every facet of the Ebola response from the beginning. This was crucially important.

Fullah explained to me how the youth community played an essential part in implementing a robust case-searcher model (physically tracing all known contacts of an individual who tested positive for Ebola and monitoring these contacts for symptoms, for a period of 21 days) and set up informal screening checkpoints to protect the community. “We instituted a strong surveillance system, robust social mobilisation mechanisms and set up taskforces in all the twelve chiefdoms”. These taskforces helped security personnel to monitor all the illegal crossing points in the chiefdom bordering Liberia after formal closure of the border in June 2014.

The initial spread of the virus in early 2014 was exacerbated by frequent crossing of international borders at the intersection of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. A region of porous borders, individuals move freely between all three countries, in some cases just to get to work. Trade was one of the key reasons for community interaction but with close family ties transcending boundaries, attendance at funerals was a regular occurrence. This enabled the virus to spread more quickly with the WHO conservatively estimating that at least 20% of all Ebola transmissions occurred due to burials. A similar scenario could have emerged in Pujehun but the district level measures to monitor border crossings, enforced by youth, prevented a repeat.

The initial spread of the virus in early 2014 was exacerbated by frequent crossing of international borders at the intersection of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone. A region of porous borders, individuals move freely between all three countries, in some cases just to get to work. Trade was one of the key reasons for community interaction but with close family ties transcending boundaries, attendance at funerals was a regular occurrence. This enabled the virus to spread more quickly with the WHO conservatively estimating that at least 20% of all Ebola transmissions occurred due to burials. A similar scenario could have emerged in Pujehun but the district level measures to monitor border crossings, enforced by youth, prevented a repeat.

Geographical location was also important. Pujehun has one of the lowest population densities in the country. Residents live in villages of less than 2,000 people, and the administrative capital has a population of just over 30,000. Added to this, the rainy season, at its peak from August, played a significant part in making access very difficult, with roads regularly impassable.

Ebola outbreaks on the continent have previously been contained because they affected small rural communities. Prior to this outbreak Ebola had officially claimed just over 1,600 victims in Africa since it was first identified in 1976. Compare that with almost 8,000 fatalities, across three countries, during this epidemic alone.

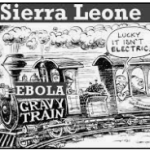

In short, Pujehun’s success relied on a pro-active district-led strategy rather than decisive central government intervention. President Koroma, not a very popular figure in the district, has not been a regular visitor. International support to the region has been small by comparison with other districts, with just one Ebola holding facility constructed.

Quick, preventative action, that placed youth at the centre, has allowed the district to escape Ebola relatively unscathed. Learning from the district’s methods should be of interest to President Koroma’s government and the international community at large, both of whom have failed to deliver a timely response to this outbreak.