In 2011, an African Development Bank report categorised one-third of Africa’s population – about 313 million people – as “middle class”.1 The term was controversially applied to those earning between US$2 and US$20 a day. The growth of a middle class in Africa has been widely celebrated in reports by international consultancies and investment banks eager to stimulate investment – and fees. A burgeoning middle class should boost tax revenues and consumer demand. It is generally considered to be good for political accountability and democracy, and a catalyst for social development, job creation, innovation and poverty reduction.

This narrative is problematic for many reasons. Middle classes are heterogeneous: their characteristics vary country by country. Most reports celebrating Africa’s rapidly growing middle class assign membership on the basis of income. But middle class and middle income are not synonymous and should not be conflated. “Class” is a socio-economic concept typically defined by many more indicators than income alone. Indeed, in contemporary Africa it is questionable whether Marxist-Weberian definitions of “class” fashioned in the West have any relevance at all.

This Counterpoint uses pay as you earn (PAYE) taxation data from the Kenya Revenue Authority to define and analyse middle-income earners in formal employment in Kenya. Individuals in this group may consider themselves, or be considered by others, to be “middle class” – or not. In 2015, they numbered fewer than 275,000 among a total population of more than 40 million. The analysis reveals important information about job creation and wage trends. It demonstrates that the number of middle-income earners, who are likely to comprise a substantial proportion of a middle class, is small and not expanding any faster than gross domestic product (GDP) growth. This has important implications for Kenya’s economic and social development.

By Kwame Owino, Noah Wamalwa and Ivory Ndekei

- MORE THAN THREE-QUARTERS OF EMPLOYED KENYANS WORK IN THE INFORMAL SECTOR, WHICH IS GROWING MUCH FASTER THAN FORMAL EMPLOYMENT

- FORMAL EMPLOYMENT IS TREADING WATER

- MOST WAGED EMPLOYEES ARE LOW-INCOME EARNERS

- WHO CAN BE (REALISTICALLY) CLASSIFIED AS MIDDLE INCOME?

- DESPITE A RAPID INCREASE IN MIDDLE-INCOME EARNERS IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR, THE MAJORITY ARE EMPLOYED IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR

- THE SHARE OF MIDDLE-INCOME EARNERS IS INCREASING IN THE PUBLIC SECTOR, BUT STATIC IN PRIVATE SECTOR

- THE PROPORTION OF WOMEN IN FORMAL EMPLOYMENT AND AMONG MIDDLE-INCOME EARNERS IS INCREASING, BUT WOMEN REMAIN A MINORITY

- MIDDLE-INCOME JOBS ARE CONCENTRATED IN SERVICE INDUSTRIES

- MIDDLE-INCOME JOBS ARE CONCENTRATED IN MAIN URBAN CENTRES

- REAL WAGES DECLINED AMONG MIDDLE-INCOME EARNERS DUE TO INFLATION

- WHILE THE REAL WAGES OF MIDDLE-INCOME EARNERS HAVE NOT INCREASED, TAXATION HAS

- THE SIZE OF THE MIDDLE-INCOME GROUP IS STRONGLY CORRELATED WITH GDP GROWTH

- CONCLUSION

- Notes

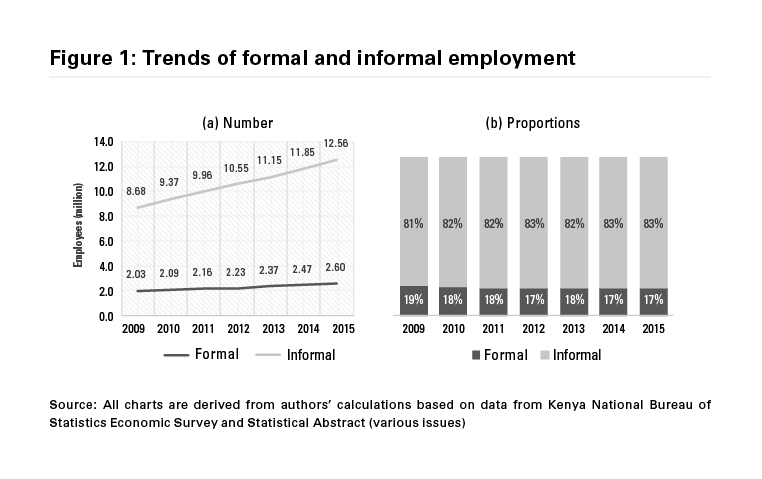

In 2009, there were 10.7 million jobs, a number that increased by 42% to 15.2 million in 2015. On the face of it, the number of new jobs might look impressive, outstripping gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging about 5% a year during the period. However, as can be seen, most new jobs were in the informal sector. While those in salaried formal employment increased by 28% from 2.0 million in 2009 to 2.6 million in 2015, the number of workers with informal jobs increased by 44% from 8.7 million to 12.6 million. By 2015, 83% of eligible workers were employed in the informal sector, an increase of two percentage points since 2009.

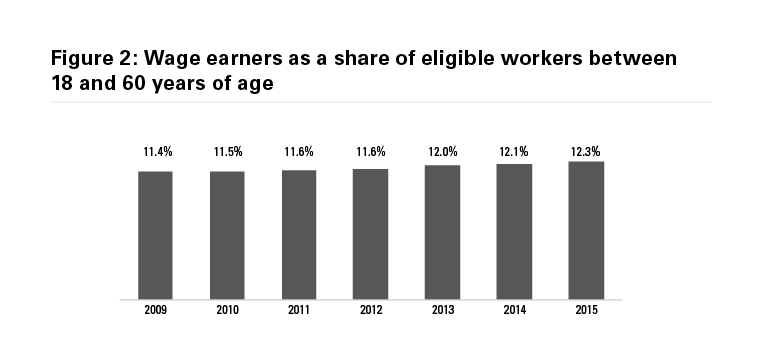

“Decent” work, as defined by the International Labour Organization, is the exception rather than the norm in Kenya. Figure 2 shows that between 2009 and 2015 the formal sector grew very little relative to the total number of eligible workers despite sustained economic growth.

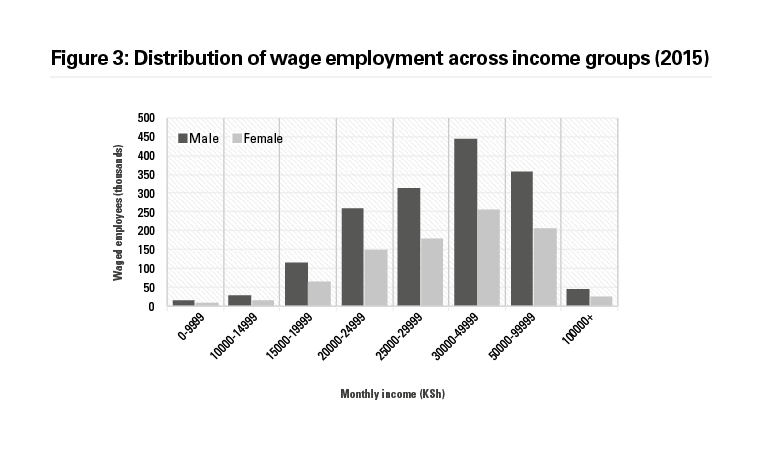

Most waged employees are low-income earners whose livelihoods are precarious. They often need to have more than one job and are in debt. Kenyans earning less than KSh50,000 (US$500) per month comprise 74% of total wage earners; 23% earn between KSh50,000 (US$500) and KSh100,000 (US$1,000) per month.2 Above that level, the number of wage-earning individuals declines rapidly. Only 3% earn above KSh100,000 (US$1,000) per month. There is a concentration of individuals who earn between KSh30,000 (US$300) and KSh50,000 (US$500) per month.

There is no universally accepted definition of middle income. Identifying an income threshold is by nature reductionist and imperfect: individuals who are very close to the boundaries of an income category are unlikely to be distinct from their peers across the boundary.Many studies use household data to analyse income groups. This has limitations, partly because of the dependence on self-reporting. For this Counterpoint, we have used pay as you earn (PAYE) tax data from the Kenya Revenue Authority. While the data self-evidently exclude anyone working in the informal sector, it is implausible that many have enterprises whose success would place them in the middle-income bracket. The Kenyan National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) verified our data.

We define Kenya’s middle-income earners in formal employment as those whose monthly earnings are between one and two standard deviations above the mean (average). Our approach is based on a number of considerations. The first is that the definition should be associated with a degree of professional capability and skills that are most probably tradable. The second is that the cohort must be sufficiently distinct from lower-income earners and those who earn far higher wages than average. In this context, the classification of middle income by KNBS as KSh24,000 (US$240)–120,000 (US$1,200) per month is so broad as to include virtually all wage earners. A lower limit of one standard deviation above the mean has been used by others and seems appropriate for Kenya, given the comparatively low incomes. A figure close to the mean would fail the test of distinctiveness and measure of professional capability.

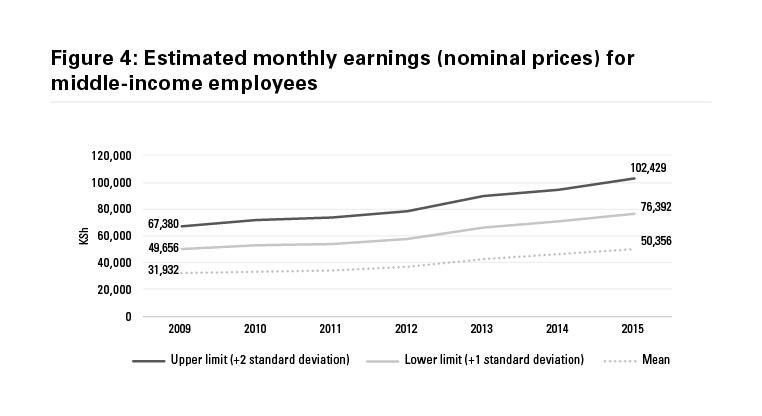

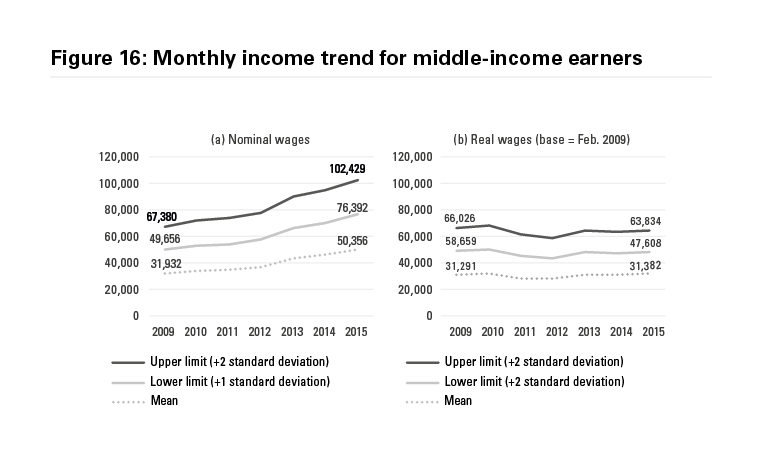

Figure 4 shows that the middle-income bracket corresponded to monthly earnings of between KSh49,656 (US$496) and KSh67,380 (US$673) in 2009 and between KSh76,392 (US$764) and KSh102,429 (US$1,024) in 2015.

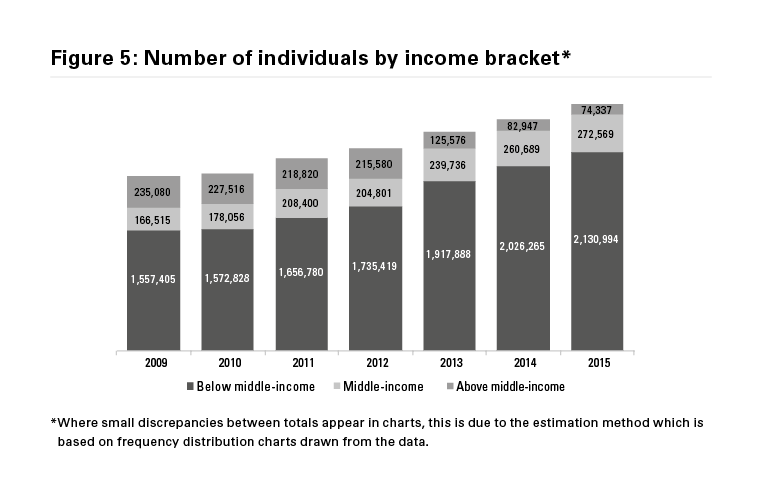

According to our definition of the middle-income bracket, the number of middle-income wage earners increased by 64% from 166,515 in 2009 to 272,569 in 2015, as shown in Figure 5 (below); and their share of the total in formal employment increased from 8.5% to 11%. The number of individuals below the middle-income group also expanded – by 36% to 2,130,994 – and its share of those in waged employment expanded from 79.5% to 86%.

There was a very substantial decline in the number of individuals in the higher income bracket after 2012. It should also be noted that the growth in the middle-income group is uneven: in 2011-2012 it contracted.

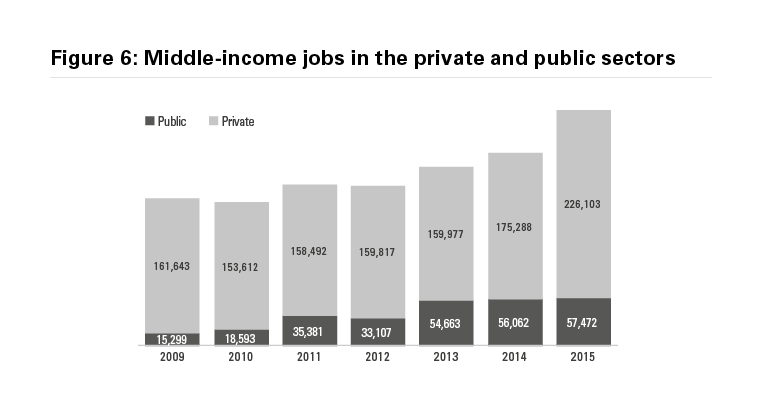

In 2009, the middle-income group comprised 15,299 individuals in public sector employment and 161,643 in the private sector. By 2015, the number of public sector middle-income earners had almost quadrupled to 57,472, whereas the number of private sector wage earners had increased by 40% to 226,103. Under the 2010 Constitution, devolution involved the creation of many new offices and commissions.About half of government revenue is spent on public sector salaries.

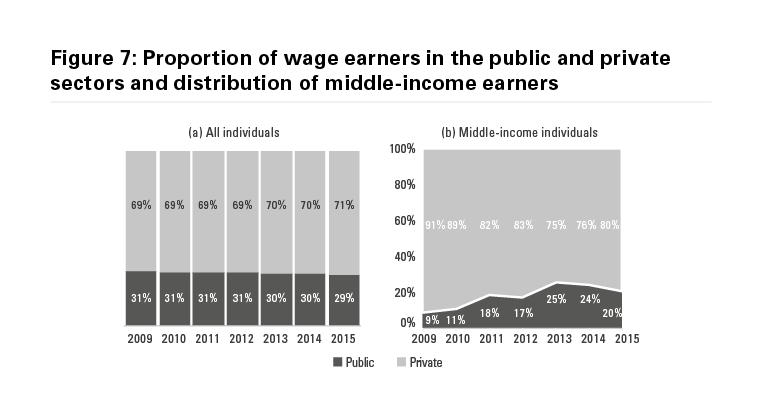

Figure 7 (a) shows the breakdown of all wage earners in the public and private sectors, while Figure 7 (b) illustrates the proportions of private and public sector wage earners within the middle-income bracket. In (b) it can be observed that the private sector accounted for 91% of middle-income employees in 2009, reducing to 75% in 2013, but then increasing by 5% to 80% in 2015.

The increase in the proportion of middle-income earners in the public sector in 2012–13 can be attributed to the provisions of the 2010 Constitution, which brought about restructuring in the public sector and the creation of new commissions, legislators and county officers. According to KNBS, the KSh19.8 billion (US$198 million) in wages the new county governments paid in 2013 was 59% higher than the KSh12.5 billion (US$125 million) sub-national government paid the previous year.3

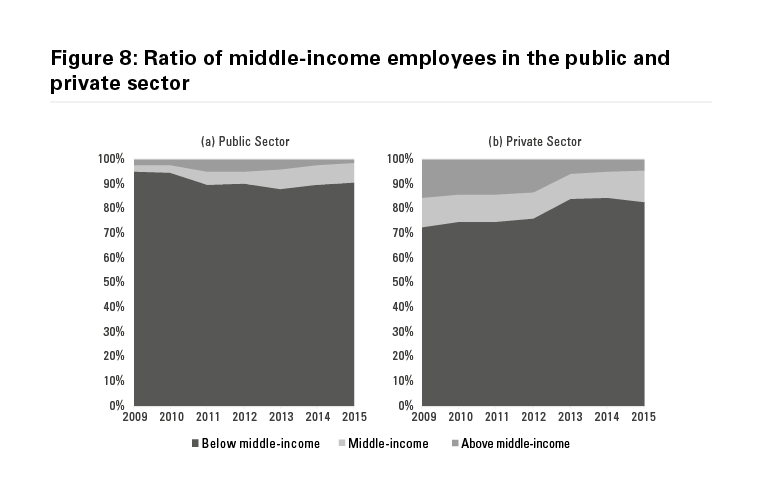

Figure 8 (a) and (b) show trends in the share of the middle-income bracket within, as opposed to between, the public and private sectors. The share of middle-income earners in the public sector increased from 2.5% to 8% between 2009 and 2015. The share of middle-income earners in the private sector remained broadly static, rising slightly from 12% in 2009 to 12.9% in 2015.

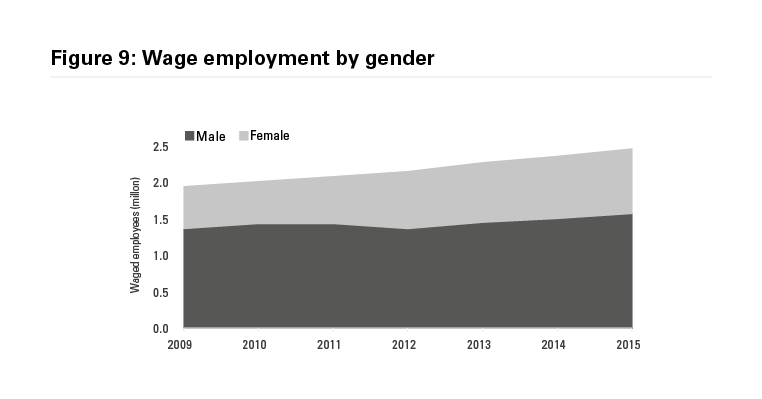

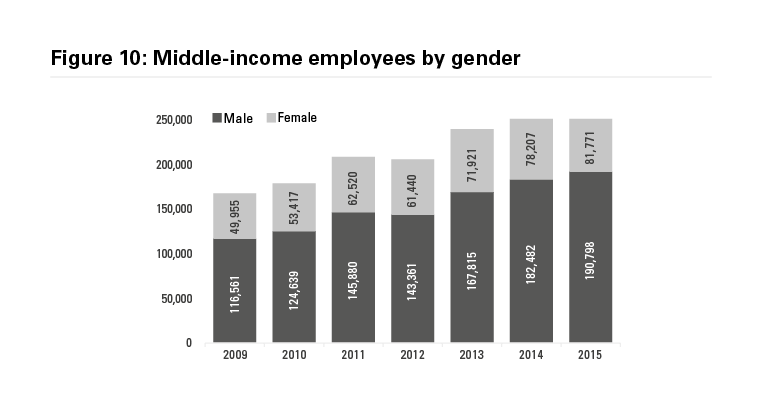

The number of women in formal employment rose by more than half between 2009 and 2015, from 0.6 million to 0.9 million, and their share rose from 30% to 37%.

However, according to KNBS data, the proportion of women in the middle-income bracket appears to have been broadly static at 30%.

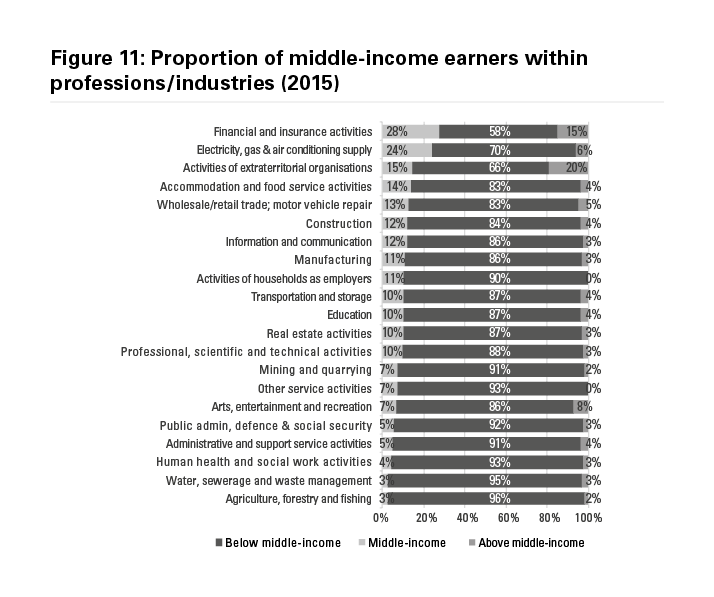

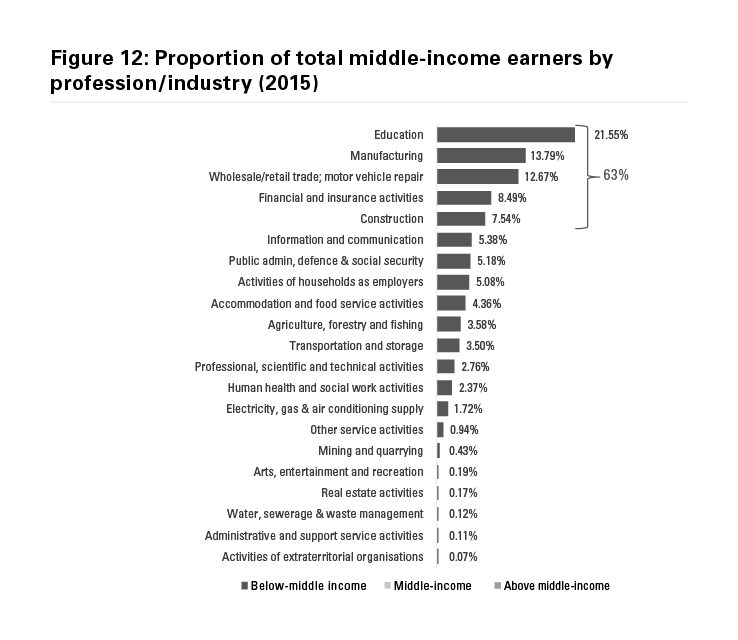

Financial and insurance activities is the sector with the highest proportion of middle-income earners (28%), followed by Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply (24%). Activities of Extraterritorial organisations and bodies has the highest percentage of individuals above the middle-income bracket (19.5%), followed by Financial and insurance activities (15%). Agriculture and Water supply and sewerage provide the lowest share of middle-income jobs (3.0%).Although Education and Manufacturing have a relatively small percentage of middle-income earners (11%) compared to Financial and insurance activities, these two sectors account for the highest number of middle-income employees because they are among the biggest employers.

Figure 12 shows that the top five sectors accounted for 63% of Kenya’s middle-income earners in 2015.

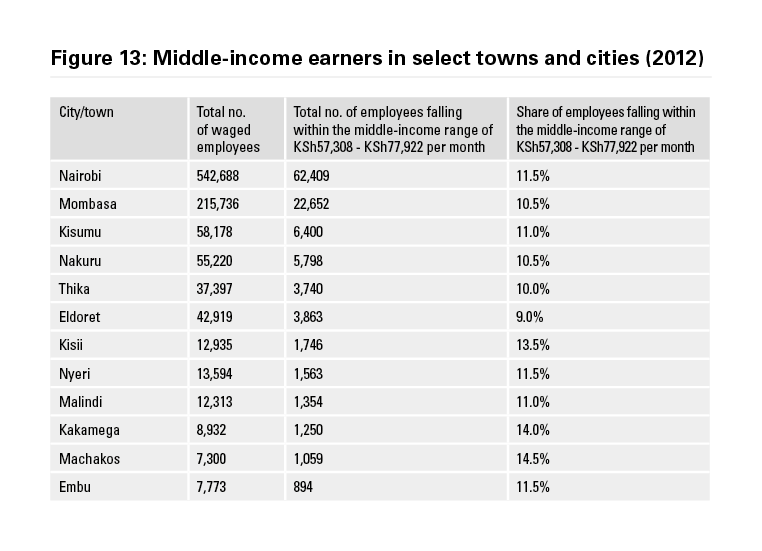

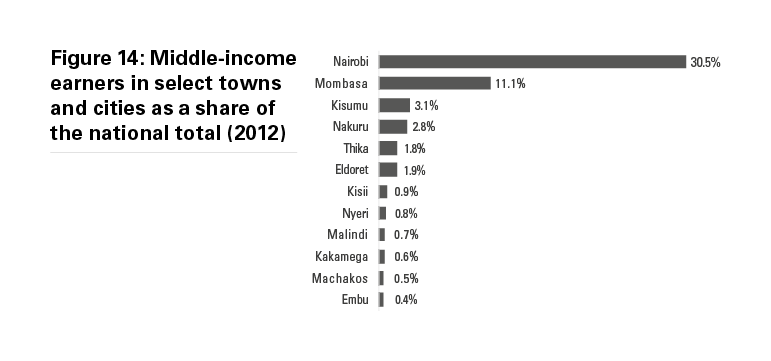

Figure 13 and Figure 14 show the distribution of formal employment and number of middle-income employees in major urban areas, mainly former provincial headquarters and cities for which there are data. Unsurprisingly, the capital Nairobi has by far the largest number of formal sector employees and middle-income earners, followed by Mombasa. Together, although home to about 10% of the total population, these two cities account for 41.6% of middle-income earners.

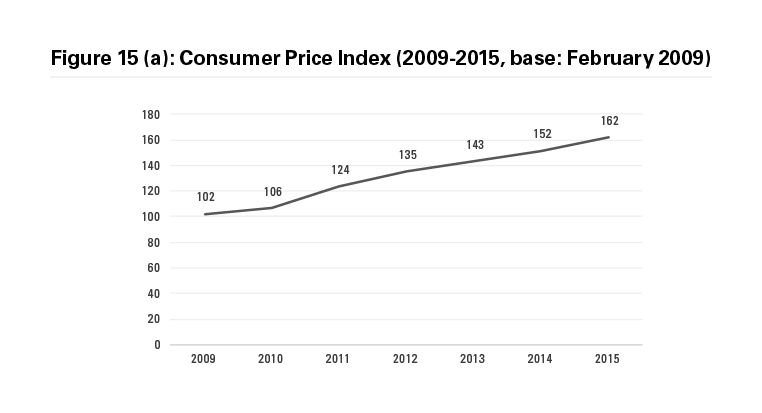

Figure 15 (a) shows that from the base date of February 2009 the consumer price index (CPI) rose by 60 points in the seven years to 2015, indicating sustained inflation.4 In the same period, total wage payments to middle-income employees increased by 172%, from KSh117 billion (US$1.17 billion) in 2009 to KSh292 billion (US$2.92 billion) in 2015 (see Figure 15 (b)).

However, the number of middle-income employees also rose, by 64%, from 166,515 to 272,569 (see Figure 5). While the increase in nominal wage payments far outstrips the increase in number of middle-income employees, this can be entirely attributed to inflation. The 57% increase in real (i.e. inflation-adjusted) wages is lower than the increase of 64% in the number of middle-income employees. In other words, real wages per capita declined among middle-income employees between 2009 and 2015. Wages for average income earners were static.

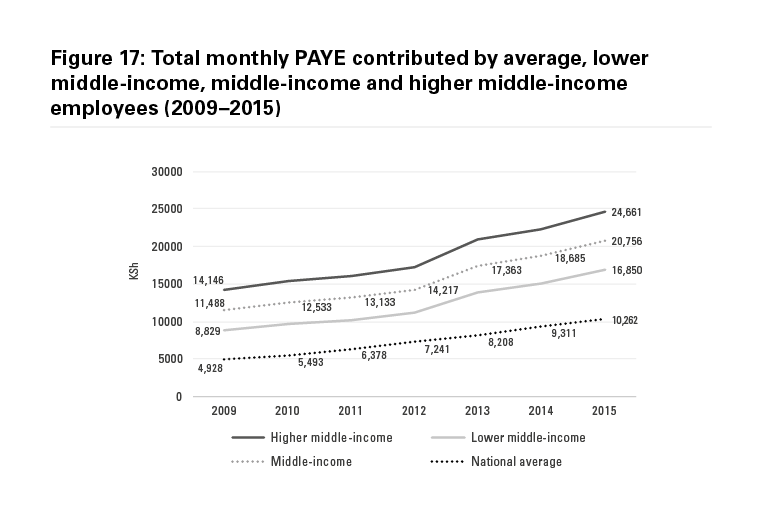

Accounting for around 40% of total tax revenue in Kenya, PAYE data is a powerful proxy for the general tax on formal sector employees because of its progressive nature. Trends in the PAYE contribution for average lower middle-income and higher middle-income employees are shown in Figure 17 below. The average PAYE contribution by all individuals in the middle-income group is also shown.

In 2009, the average monthly amounts of PAYE taxation paid by higher and lower middle-income earners were KSh14,146 (US$141) and KSh8,829 (US$88) respectively. In 2015, the average monthly deductions at source had increased to KSh24,661 (US$247) and KSh16,850 (US$168) respectively. The average monthly PAYE for all wage earners in Kenya more than doubled from KSh4,928 (US$49) to KSh10,262 (US$103).

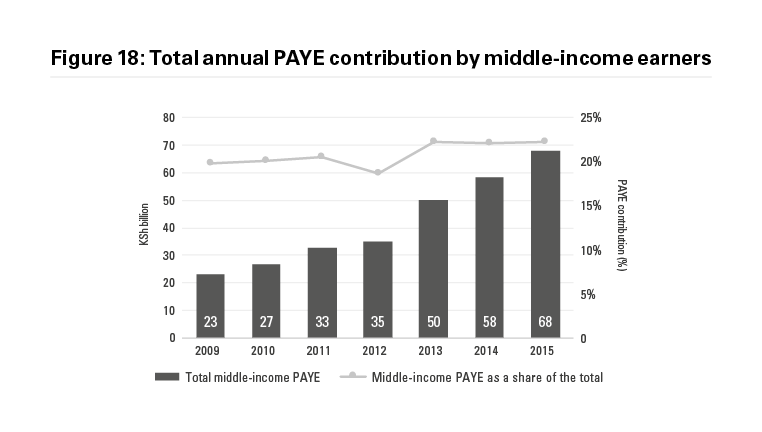

The total annual PAYE contribution by middle-income earners almost tripled from KSh23 billion (US$230 million) to KSh68 billion (US$680 million) between 2009 and 2015. This compares to an increase in the number of middle-income earners of 64%, from 166,515 to 272,337 individuals. Middle-income PAYE as a share of total national PAYE increased from 20% in 2009 to 22% in 2015.

Notably, average earners saw their tax rate rise the most during the seven-year period, from 15.4% to 20.4%.

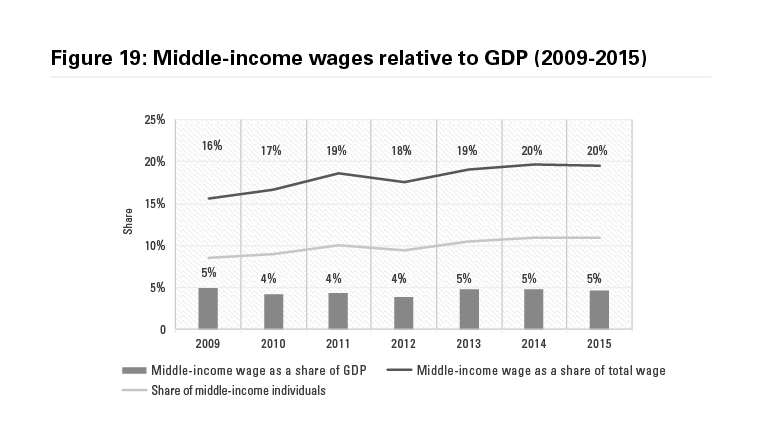

There is a strong correlation – indicated by a coefficient bracket of 0.97 – between GDP growth and the number of middle-income earners. Figure 19 shows that total wages earned by middle-income employees were 4–5% of GDP throughout the seven-year period.

Kenya has the fourth-largest economy in sub-Saharan Africa after Nigeria, South Africa and Angola. Successive governments have promoted economic growth as the main driver of job creation. The national development plan, Vision 2030, aims “to transform Kenya into a newly industrialising, middle-income country providing a high quality of life to all its citizens”.Employment is increasing in Kenya, but formal jobs are not being created by labour-intensive industries and wage earners remain predominantly low income. More than three-quarters of all jobs are in the informal sector, which is growing far faster than waged employment in the formal sector. By and large, formal employment is treading water: despite sustained economic growth, the increase in the proportion of decent jobs relative to the total number of eligible workers is negligible.

If dynamic job creation and structural transformation of the economy were taking place it would be reasonable to expect to see rapid expansion of the number of middle-income earners and their share of the salaried workforce. In 2015, fewer than 275,000 individuals earned between KSh76,392 (US$764) and KSh102,429 (US$1024) per month – 11% of all Kenyans in formal employment. This small group is concentrated in the private sector, in service industries and in the two main cities. Inflation completely eroded wage growth in 2009–15, but taxation increased. Total wages earned by middle-income employees are increasing at no greater rate than GDP growth.

Decent jobs are essential for poverty reduction and social and economic development; and to generate increasing tax revenue to finance that development. The failure to stimulate a surge in decent jobs is a pressing concern. The working age population is forecast to increase by nearly nine million people between 2015 and 2025,5 a number almost equivalent to the entire informal sector in 2015. Furthermore, as most jobs are of necessity being created in the informal sector, Kenya’s labour productivity is low and static, indicating that while there is GDP growth the quality of the labour force is worsening. This situation presents a conundrum: labour productivity has to rise for incomes to rise.

To return to the debate about emerging middle classes in Africa, an intention on the part of policymakers to foster a growing middle class is welcome. But it is not useful to proclaim that a burgeoning and thriving middle class exists when the evidence for rapid growth in the number of middle-income earners relative to all wage earners and the working age population is non-existent. By analysing middle-income earners, this Counterpoint asserts that this is largely the case in Kenya. The structure of the economy is little changed since independence. Unfortunately the myth of a growing middle class merely shields decision-makers from answering for their failure to create decent jobs and greater prosperity.

1. African Development Bank, “The Middle of the Pyramid: Dynamics of the Middle Class in Africa”, 2011

2. The average exchange rate for 2015 was US$1:KSh98.2 (Central Bank of Kenya statistics). A rounded rate of US$1:KSh100 has been used throughout for guidance

3. Kenya National Bureau of Statistics Economic Survey 2016 p.76

4. CPI figures as at fiscal year end (March)

5. World Bank, “Kenya – Jobs for Youth”, Report No. 101685-KE, February 2016, p.8

Kwame Owino is chief executive officer of the Institute of Economic Affairs – Kenya; Ivory Ndekei is programme officer (regulation and competition) and Noah Wamalwa is assistant programme officer (public finance management) at the same institution.