Ghana is one of Africa’s most urbanised – and rapidly urbanising – countries. In the past three decades, the number of city dwellers has risen from four to 14 million; more than 5.5 million live in slums. Urban growth exerts intense pressure on government and municipal authorities to provide infrastructure, affordable housing, public services and jobs. It has exacerbated informality, inequality, underdevelopment and political patronage. Some commentators warn of an impending urban crisis.

Policymakers and international donors continue to prescribe better urban planning, slum upgrading, infrastructure investment and “capacity building” to “fix” African cities. While these are necessary, the success of any urban strategy depends on an informed appraisal of the political dynamics of urban neighbourhoods that define governance in Ghana’s cities.

Slums will play an increasingly important role in Ghanaian politics. They create opportunities for politicians, entrepreneurs, traditional authorities and community leaders. Migrants and settlers make competing claims on land and ownership, forming new communities and constituencies in the process. Informal networks pervade formal political institutions and shape political strategy.

Political clientelism and the role of informal institutions are deepening alongside the strengthening of formal democratic institutions. Yet the way that urban neighbourhoods are really governed, how “hidden” informal networks interact with formal politics, and how citizens hold their leaders to account, are too often overlooked.

By Mohammed Awal and Jeffrey Paller

Ghana is widely regarded as a successful model of multi-party democracy in Africa. The country has an active legislature with a strong and credible political opposition; an independent judiciary; growing, free and vibrant media that provide extensive coverage of public affairs and fierce debate of political issues; and an assertive civil society. Among its defining features is the conduct of successive, relatively free and fair competitive multi-party elections, with peaceful transfers of power. In 2008, John Atta-Mills won the presidential election in a run-off by just 0.46% of votes cast; in 2012, the margin of victory was less than 3%.

In 1988, Ghana embarked on a comprehensive decentralisation programme to bolster democratisation, devolve resources and encourage a more participatory approach to local development. The country is administratively divided into 10 regions and 216 districts, with three tiers of sub-national government at regional, district and sub-district levels. At the district level Metropolitan, Municipal and District Assemblies (MMDAs) are responsible for development planning, revenue collection, service delivery and internal security. Decentralised local governance is presented as an effective response to local administrative and development needs.

Democratic governance is not benefiting the public good

Despite the apparent success of democratisation, Ghana’s political framework combines multi-party politics and entrenched clientelism rooted in informal networks. The system generates intense competition between ruling and opposition coalitions, which strains relations between party elites and lower ranks, weakens institutions and leads to poor commitment to effective devolution. It encourages ruling elites to pursue short-term strategies to win elections, at the expense of long-term policy choices that might deliver inclusive economic growth to mitigate inequality, unemployment and poverty reduction.

Economic policy and management have failed to deliver macroeconomic stability or appropriate responses to the continued informalisation of the economy.1 Election-related fiscal indiscipline is normal. Moreover, rent seeking and corruption, particularly by the country’s ruling and bureaucratic elites, have become more pervasive. Democratic governance is not benefiting the public good.

The transfer of power and responsibilities to sub-national government remains incremental, paradoxical and challenging. Problems of accountability, institutional autonomy, participation and poor service delivery typify local government across the country. While the rhetoric of decentralisation speaks of making democracy a reality, the process has in effect been used as a political tool to maintain central government control, investing significant powers in non-elected authorities and sustaining a patronage system developed over decades that undermines the nation’s already weak institutions. Politicians, mayors, and traditional authorities use MMDAs, which comprise elected and appointed members, as a means to further personal and party interests.

Under the current system of decentralised governance, citizens – particularly the poor – are limited in their ability to influence policy, monitor government and hold it accountable. While citizen participation is at the core of Ghana’s decentralised system in law, the scope for civic engagement is in fact limited, selective and state defined. Citizens and civil society have to wrestle political space for themselves. Influence can be exerted through informal networks that not only pervade formal political institutions but also shape the behaviour of political actors. Democracy in Ghana is best understood as a dominant presidential system reliant on informal networks.

“Competitive clientelism” and the associated power struggles that take place in the ranks of Ghana’s political parties have negative consequences for urban governance.2 Local assembly representatives are formally apolitical, but have close ties to political parties – and party priorities often direct resources into election campaigns, rather than investing in roads, streetlights or other public goods. While governance is formally structured, the distribution of political power takes place outside official channels.

Competition for power in Ghana has become increasingly intense, especially in cities, with more resources at the government’s disposal and greater sophistication in how political parties mobilise support. “Toilet wars” in Accra and Kumasi are a good example of this strong competition between rival party activists and loyalists for the control of a public service – to the detriment of consistent, universal provision of that service.3

Ghana is one of the most urbanised countries in Africa. According to World Bank data, in 2014 53% of the population lived in towns and cities. The country has urbanised rapidly: since 1984, the urban population has increased from four to 14 million, with an estimated 5.5 million (39%) living in slums.4 During the colonial period and into the independence era, city planning in Accra did not take indigenous and migrant communities into account. They were largely ignored by the state and left unregulated. Even today, planners refuse to accept the legality of slum settlements.

Rapid urbanisation exerts pressure on governments to provide jobs, housing, transport and other public services. Despite the deepening of democracy and political decentralisation in Ghana, urban neighbourhoods are under-resourced and informal economic and political networks dominate. But the growing urban population and its associated socio-economic and political dynamics have made Ghana’s cities central to the country’s political, governance and development processes.

Citizens interact and engage with elected officials, but not always in conventional ways

In an April 2013 survey of 16 Accra slum communities, 94% of respondents had a voter identification card, 24% had a passport, 48% had a bank account and 42% had a national identification card.5 Two-thirds were employed in the informal economy. The results of the survey run contrary to portrayals of slums as havens for vagrants and criminals cut off from the state. The role of the state and the relationship between informal networks and government officials merits close attention. Citizens interact and engage with elected officials, but not always in conventional ways. Slum politics is messy, complex and misunderstood.

The consolidation of multi-party politics is giving way to entrenched urban political machines. Cities offer politicians large voting blocs – and more. Parties rely on activists, “foot soldiers” and “macho-men” to patrol polling stations during voting and registration periods, attend rallies and mobilise voters.6 “Political parties find muscle [in slums]”, explained former Accra mayor Nat Nunoo Amarteifio; “we [in the municipality] also had our own connections with them”.7

In their influential volume Africa’s Urban Revolution, Susan Parnell and Edgar Pieterse write: “Learning where power lies in the city can be as challenging as persuading those in power of the need for change”.8 The majority of studies on African urban politics and planning emphasise the need for institutional change without first uncovering the roots of power. Policymakers devise lofty schemes to transform property rights, elections, administrative duties and economic regulation without understanding the role of existing incentives and where power lies. While this “grand” reform agenda is necessary, the success of any urban policy reform depends on a proper understanding of the political economy that underlies the power and political dynamics of cities.

Elections serve as an important context for political jockeying and competition – both central aspects of democratic governance. However, the way Ghanaian citizens really hold their representatives to account is often ignored. There is a failure to capture the meanings that leaders and followers attach to the political process, thereby neglecting the expectations that citizens have of their leaders and the incentives that motivate their representatives in the struggle for political power. There is a great deal more to the practice of politics in urban communities than casting votes.

The way Ghanaian citizens really hold their representatives to account is often ignored

Christianity has emerged as a powerful force in Ghanaian politics. In January 2012, Edwin Nii Lante Vanderpuye of the National Democratic Congress (NDC), a candidate in the contest to become the member of parliament (MP) for Accra’s Odododiodio constituency, held a late-night prayer service at the Missions to Nations Church. The constituency is one of 27 in the Greater Accra Region and includes the Ga Mashie and Old Fadama slums. The Odododiodio Network of Churches sponsored this public and symbolic event.

Vanderpuye’s objective was to gain “spiritual support” for his bid. As he embarked on his campaign, he asked for God’s help in making the constituency better; his religiosity increased his appeal as a community leader and bolstered his electoral chances. Residents understood that although the candidate’s education and occupation were important, “what he really needs, what really matters, is the spiritual vote”.9

Historically, family lineage, in contrast to the performance of government, ideology or even programmatic ideas, has been the most decisive factor in the selection of a leader. In this respect, Vanderpuye already had an implicit advantage over his rivals as a member of the Lante Djan-We clan, the first to celebrate the Homowo Festival, the most important annual ceremony for the Ga people.

Having established and reaffirmed his strong personal links to the community, Vanderpuye set about building a political family. As an aide to former president John Atta Mills, he used his personal networks to create economic and educational opportunities, especially for young voters. He paid school fees for children in the community and contributed financially to funerals and birthday parties of influential, politically connected residents. Vanderpuye also supported the establishment of athletic and social clubs to organise disparate clusters of young people who were frustrated at the performance of the incumbent MP. In the words of one voter: “It is not that he is rich, but he has a link… He’s all around. When you go to Brong Ahafo, he has friends. Go to Western, he has friends. Go to the North, he is known there”.10

Informal institutions underlie – and are defining characteristics of – the democratic process in urban Ghana

During the election campaign, Vanderpuye handed out rice, clothes and other small gifts at rallies. He paved the alleyway in front of his family home and claimed that he would do the same for the entire community if he was voted in. This complemented the familial language he used in speeches and further personalised local politics.

Vanderpuye’s strategy proved especially effective among younger voters and he defeated his rival by 19,698 votes, securing 63% of the vote. The conduct of his campaign exemplifies how informal institutions underlie – and are defining characteristics of – the democratic process in urban Ghana. Victory rested on the support of personal networks: Vanderpuye did not promise public goods for all, but improvements and opportunities for certain communities in return for their backing.

The margin of victory for Vanderpuye was deceptively large: the campaign was contentious throughout. Elsewhere in Accra, electoral battles were conducted on similar lines and some were even more closely fought. In Ayawaso Central – which includes the slums of Alajo, Kotobabi and parts of New Town – New Patriotic Party candidate Henry Quartey won by just 635 votes out of a tally of 66,859. The NDC’s Nii Armah Ashietey won Korle Klottey, where the Abuja and Avenor slums are located, by 1,275 votes out of a total of 74,407.

Aspiring political leaders in Ghana spend a long time building a following. Typically, they step into formal positions of power only after proving their credentials by serving their neighbourhoods for many years. Informal authority rests on “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels”.11 These rules constrain and enable the behaviour of residents over time and transcend ethnicity, class and political affiliation. Leaders, including politicians and chiefs, build support by extending their social networks, accumulating wealth, being family heads and religious figures – they are friends, entrepreneurs, parents and preachers.12 Personal rule persists in Ghanaian society despite the strengthening of formal democratic institutions.

Politicians in urban constituencies make strategic calculations to gain the support of slum dwellers, as Vanderpuye’s campaign exemplified. They visit slums to show solidarity with victims of fires and floods; distribute food and clothing to vulnerable populations, such as kayayei (head porters); attend “outdoorings”, funerals and weddings of local leaders; and pray with pastors and imams at local churches and mosques. Showing influence and possession of the financial resources to improve the lives of residents is increasingly important. Individuals and social groups receive private or “club” goods on the basis of their support for a political party or candidate. This relationship weakens issue-based pressure, allowing political elites to shy away from responding to major structural challenges, and greatly politicises development.

Everyday interaction is a crucial – but poorly understood – component of how accountability is generated between leaders and citizens in the absence of formal mechanisms. It better reflects how Ghanaians understand and experience “accountability as public, relational and practised in the context of daily life”.13 Accountability is much more than just voting leaders out of office.

Complex, shifting interactions enable citizens, community leaders, and municipal workers alike to demand their “democratic dividend”

Formal mechanisms of democratic accountability are seldom accessible for the poorest. But urban residents have found other ways to hold leaders to account that fit within informal networks and social norms. Slum neighbourhoods are not homogenous, but collectively they are increasingly important providers of opportunity for many different types of people and organisations. Complex, shifting interactions enable citizens, community leaders, and municipal workers alike to demand their “democratic dividend”.

“Dignified public expression”14 based on respect, rather than the implicit threat of removal from office, forms the basis of complex constituent–representative relations and political accountability in Ghana. It is relational and practised in the context of daily life. It fosters individuals’ belief that collective action will make a difference and provides an important means of translating information or needs into action. A dynamic process of talking and listening between constituents and representatives characterises Ghana’s urban politics.

In Akan-Twi, Ghana’s most widely spoken indigenous language, the word for democracy – Ka-bi-ma-menka-bi – translates as “I speak and then you speak”. For many Ghanaians, democracy is the process of free political expression between equals. It ensures that those who are affected by decisions are included in the decision-making process. Bonds of respect must develop between representatives and constituents, reinforced by concepts of reciprocal claim-making, shame and honour. Trust is generated if leaders are able and willing to give an account of their actions.

Political accountability is therefore a complex web of a community’s overall trust in a leader and its perception of the leader’s ability to get things done. In the words of a focus group participant in Agbogbloshie:

“A good assemblyman is one that listens to people when they call on him, one that calls the people to meetings to discuss ways to improve… one who listens to your plight anytime you call on him even at night, one that will come to your community and when you call him, take your concerns and present them at the assembly, so as to make sure all your problems are solved.”15

It is important to note that patron–client relations and practices developed well before multi-party politics, and were particularly evident during the national struggle for independence. Structures of local authority that have developed through a long, historic settlement process have not been replaced by “modern” elections.

The struggle for political power in Ghana’s cities hinges on the control of access to housing and the provision of tenure security. This is most readily apparent in Accra. Historically, neither the state, nor private developers have been able to meet demands for secure, quality and affordable housing. UN-Habitat estimates that 5.7 million new rooms are needed in Ghana by 2020. At present, up to 90% of housing is built and governed informally, outside of local authority control.16

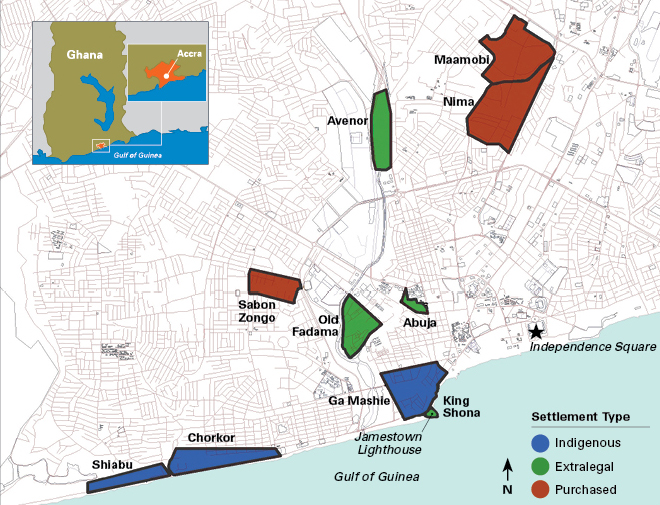

Three types of informal settlement exist in urban Ghana: extra-legal, indigenous, and purchased or legitimate (see map).17 The type of settlement determines sources of legitimacy and authority. Ownership of property is in the hands of non-state providers, who rely on local informal social networks embedded in daily community life. They have withstood and adapted to the arrival of multi-party politics; indeed, the expansion of political parties in Ghana has strengthened their power.

In a context of weak formal institutions and an acute housing shortage, local leaders establish territorial authority by founding new neighbourhoods, taking in migrant “guests” and strangers, selling land as de jure or de facto landlords, and serving as representatives and speakers for social networks and interest groups. In all slums, leaders can gain legitimacy by resolving property disputes, thereby achieving status and prestige, while also extracting rents from claimants and defendants.

In purchased settlements – regarded by the authorities as legitimate because of the way in which the neighbourhood’s land was acquired from customary authorities – landlords have an incentive to provide housing to those who need it. Providing affordable and secure housing to followers increases their legitimacy and authority, giving them the necessary political capital to compete for formal positions of power. Unusually for an African city, in Accra housing in purchased settlements is administered as a common or public good.

In indigenous settlements – neighbourhoods governed by customary norms of the ethnic group – traditional authorities benefit from selling land to the government at inflated prices. The ambiguity of the land tenure regime allows them to allocate land multiple times and to demand rents and tributes. Recognised by the state as legitimate owners, landlords are not incentivised to go through formal channels to secure goods and resources. Instead they use the powerful political resource of indigeneity to secure developments for their own, not the wider, community. Housing is administered as a club good.

Landlords in most slum communities serve as parental figures in people’s daily lives

Extra-legal settlements – neighbourhoods that the government has not authorised and are illegally inhabited – provide young social and political entrepreneurs opportunities to make money, develop a following and amass power. By taking advantage of insecure and informal property rights they can operate “public services” such as shower and toilet businesses, scrap recycling and transport. In Old Fadama, for example, there are approximately 400 shower operators.

Extra-legal settlements are not entirely “off the map” in the way that is often portrayed. Government officials own land and businesses in these communities and residents are often tipped off about imminent evictions. Politicians and state bureaucrats empower local political entrepreneurs by protecting de facto landlords in exchange for political support. Housing is administered as a private good.

Insecure property rights provide the urban poor unique opportunities to start businesses, control housing markets, and govern resources and services. These opportunities are not equally accessible to everyone, but depend on local power dynamics. Landlords in most slum communities serve as parental figures in people’s daily lives and can provide security and protection; for example, to young migrants and others in need of work. As one resident explained: “If you have a problem you just go to him. Even if he does not solve it, he will guide you to solve it”.18 Understandings of security of tenure coincide not with the formal housing market and state-sanctioned land access, but with informal norms of legitimacy and authority.

Land ownership and control lie at the heart of grassroots political struggles

Although in some cases landlords serve as party representatives, assembly members or MPs, more commonly they act as brokers between politicians and residents. In Accra, they function in the system that the well-organised NDC “machine” orchestrates and oversees. Land ownership and control lie at the heart of grassroots political struggles. In a context where goods and services are mostly distributed privately through entrenched networks of political patronage, state-organised schemes to build multi-storey tenements and create individual title for all residents threaten control and authority. They can undermine landlords, divide communities, and contribute to deadlock and the persistence of informality.

Local land and property disputes are not trivial. They are the reason that ambitious slum-upgrading schemes stall or do not work for the benefit of those slum dwellers who are most in need. Property disputes have threatened the success of the UN-HABITAT-sponsored Slum Upgrading Facility in Ashaiman; severely slowed the process of upgrading Ga Mashie; and entirely stymied plans for improving Old Fadama. The provision of public services and access to housing remains a central issue that divides groups in slums and is further politicised in the era of multi-party politics.

Slums are the products of failed policies, bad governance, corruption, inappropriate regulation, dysfunctional land markets, unresponsive financial systems and a fundamental lack of political will. Each of these failures adds to the toll on people already deeply burdened by poverty, and constrains the enormous potential for human development that urban life offers.

Many planners and policymakers assert that Ghana’s cities are in crisis. This is a simplistic, over-dramatic depiction. Urban neighbourhoods are certainly under-resourced and dominated by informal economic and political activity. But they also offer significant political and economic opportunities, and scope for change.

The grassroots political economy and social and political networks that govern urban Ghana are central to achieving sustainable and inclusive urban development. This is especially true in the case of providing adequate affordable housing. Before ambitious slum-upgrading schemes will work, underlying land tenure issues must be resolved. This requires political solutions that have winners and losers, rather than the merely administrative or technical ones that organisations such as the World Bank, UN-Habitat and other international NGOs advocate.

Ghanaian city dwellers need to have incentives to follow policy prescriptions and play by “official rules”. Registering land and businesses should be profitable. Relocation to new neighbourhoods should consider local architectural, social and economic preferences. Providing public goods and services to newcomers should accrue electoral advantages. These are just a few suggestions. Planning and finance are not the foremost problems: poorly understood politics is.

1 Awal, M., “Ghana: Democracy, Economic Reform and Development, 1993-2008”, Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 14 (1), 2012, pp. 97–118.

2 Whitfield, L., “Competitive clientelism, easy financing and weak capitalists: The contemporary political settlement in Ghana”, Danish Institute for International Studies (DIIS) Working Paper, 27, 2011.

3 Ayee, J., and Crook, R., “‘Toilet wars’: urban sanitation services and the politics of public-private partnerships in Ghana,” 2003.

4 World Bank, “Rising through cities in Ghana”, Apr. 2015.

5 Paller, J., “African Slums: Constructing democracy in unexpected places”, PhD Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2014 (unpublished).

6 Bob-Milliar, G., “Political party activism in Ghana; factors influencing the decision of the politically active to join a political party”, Democratisation, 19 (4), 2012, pp. 668–89.

7 Interview with Jeffrey Paller, 22 March 2012.

8 Parnell, S., and Pieterse, E. (eds), Africa’s Urban Revolution, Zed Books, 2014, p. 10.

9 Informal conversation with Ga Mashie resident, Accra, 18 January 2012.

10 Interview with Rev. Robert Esmon Otorjor, Accra, 27 June 2012.

11 Helmke, G. and Levitsky, S., “Informal Institutions and Comparative Politics: A Research Agenda”, Perspectives on Politics, 2 (4), 2004, pp. 725–40.

12 Paller, J., “Informal Institutions and Personal Rule in Urban Ghana”, African Studies Review, 57, 2014, pp. 126-8.

13 Paller, J., “Dignified public expression: The practice of democratic accountability”, Working Paper (unpublished), p. 6.

14 Ibid.

15 Focus group discussion participant, Agbogbloshie, 9 June 2012.

16 UN-HABITAT, “Ghana housing profile”, 2011.

17 Paller, J., “Informal Networks and Access to Power to Access to Power to Obtain Housing in Urban Slums in Ghana”, Africa Today, 62 (1), 2015, pp. 31–55.

18 Focus group discussion participant, Tulako-Ashaiman, 3 June 2012.