This is a guest blog by Kieran Holmes, who is Commissioner General of Burundi’s semi-autonomous revenue authority, the Office Burundais des Recettes. Kieran recently co-authored an ARI report detailing OBR’s efforts to reform tax collection and administration in one of Africa’s poorest nations (available either in English or French).

African governments must be able to mobilise revenues from taxation if they are to achieve long-term development. Domestic sources of income are crucial for funding social services aimed at poverty reduction and lessening dependence on foreign aid. Countless studies have shown that efficient tax systems help to strengthen state capacity and promote good governance.

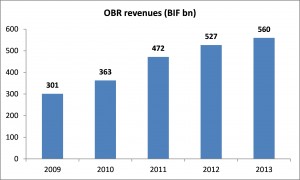

For the past four years, I have been the Commissioner General of the Office Burundais des Recettes (OBR), the revenue authority of Burundi. In this period, taxes collected by the OBR have increased by 86%. An initial target to increase the contribution of tax revenue to GDP by 1% by 2016 was achieved in 2011. Tangible public services are now being delivered using this money. Corruption in revenue administration has reduced significantly. These are remarkable achievements for an institution in a small, post-conflict country where four-fifths of the population subsists below the US$1 per day poverty line.

The OBR is a real success story for the development industry. For every US$1 invested by Trade Mark East Africa (TMEA) – the body through which the majority of donor assistance is channelled – an additional US$8.30 in revenue is collected by the OBR. Some £14 million of aid funds has been spent to date on the OBR and I argue that this is real value for money.

Alas, all of this vital work could soon be undone. Donor organisations have yet to agree the second phase of support in line with the OBR’s strategic objectives, a reality that threatens to undermine all of the achievements of the first phase.

For the last three years, Burundi has been amongst the top ten best reformers in the World Bank’s Doing Business Index, often the only African country in the top ten. It is now possible to form a business in Burundi inside of one hour. New income tax, VAT and tax procedures laws were promulgated in 2013 and significant tax harmonisation with the rest of East Africa has occurred – Burundi’s top rate of tax is now a very competitive 30%.

One-Stop Border Posts (OSBPs) have been introduced with Burundi’s East African Community (EAC) neighbours, Rwanda and Tanzania. A new computer system and a scheme for permitting compliant taxpayers to rapidly clear their goods, mean Burundi is well poised to take advantage of the wider trade opportunities in the EAC. Border clearance times have been reduced. Very soon truck drivers will not need to exit their vehicles to clear goods at border crossings.

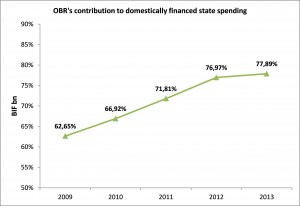

The OBR’s contribution to Burundi’s domestically financed state expenditure has grown from 63% in 2009 to 78% in 2013. Whilst Burundi still needs external assistance, this remains a significant step forward for one of the poorest countries in the world.

How has the revenue growth been achieved and what are the lessons to be learned for other states?

OBR recruited an almost entirely new cadre of 425 professional staff and these were trained using personnel from neighbouring revenue authorities and external advisers. Entirely new working conditions were crafted and a strict Code of Conduct introduced. The OBR adopted a salary scale that reflected the professional work people were asked to do. Modern procedures for tax and customs work were employed. Everyone has been obliged to work in open-plan offices which have created the right atmosphere of transparency. These processes have been documented in detail by Africa Research Institute.

The first phase of donor assistance channelled through TMEA amounted to US$17 million. This included financing for the position of the first Commissioner General, new computer systems, capacity building, office renovations and adviser assistance. The latter came in the form of technical expertise in taxation, customs, human resources, auditing, information technology, procurement and communications. The technical assistance alone cost roughly US$10 million. However, expressed as a percentage of the additional revenue generated between 2010 and 2013, the adviser assistance comes to just 2.17%.

The OBR’s recurrent operating costs are financed primarily by the state, including staff salaries, rent, consumables and travel. This has never exceeded 3% of the revenue collected by the OBR. In 2013, due to budget cuts, this figure fell to 2.3% and it will fall again in 2014 unless promised additional funding materialises.

Sadly, the OBR faces the perfect storm in 2014. In addition to a severely curtailed domestic budget, the current international development assistance to the OBR will end in May. The contracts of all technical assistants expire by then and for procedural reasons these are not being renewed. Even if new advisers are successfully recruited there is likely to be a substantial break in support.

Successful revenue reforms elsewhere have taken up to 12 years – or more. In order for the OBR to grow sustainably, it needs the financial stability to make its own strategic decisions as defined in its 2013-2017 Corporate Plan. These objectives have been defined locally in conjunction with the Board of OBR and the Government of Burundi, and embraced by the international community.

Will Burundi’s brief period of revenue reform be the proverbial candle in the wind or will sufficient new donor funding emerge to take the OBR, and Burundi, to the next stage of development? I fear the worst. And am I to be proved right, the donor community would have wasted its best opportunity to reduce poverty in the long-term in Burundi.

Kieran Holmes is the first Commissioner General of the OBR. He may be contacted at Kieran@kieranholmes.com You can follow him on Twitter at @kieran_holmes

FURTHER READING:

For state and citizen: Reforming revenue administration, in Burundi (in English / in French)

Tax in Africa: In conversation with Kieran Holmes (in English / in French)