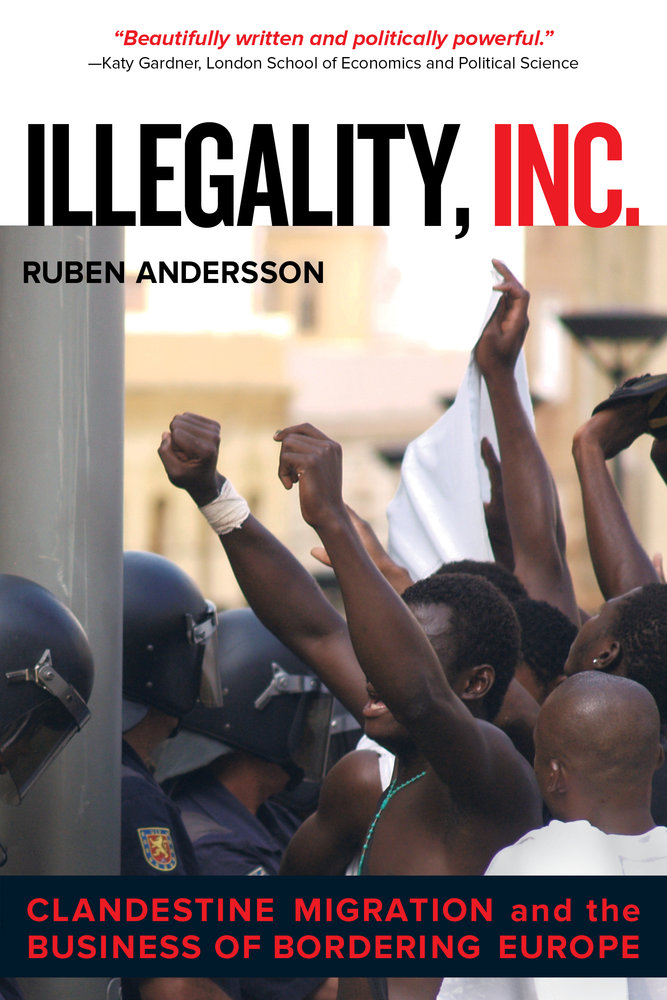

In August 2006, 6,000 migrants arrived on the shores of the Canary Islands in old fishing vessels from Senegal and Mauritania. The influx brought the issue to the attention of a global audience. The response from FRONTEX, the EU border agency that ensures the integrity of Europe’s borders, helped stemmed the flow of migrants from Senegal and Mauritania into Spanish territories. However, in August 2014, nearly 1,000 people were intercepted by the Spanish coastguard in 72 hours off Gibraltar, as they attempted to complete the final nine miles of a journey that, for many, will have begun in West Africa, from Morocco to Spain.

Andersson’s account begins at the source of this first wave of migration, in the coastal communities of Senegal. He argues that an illegal migration industry has developed in response to the perceived burden migrants pose in three areas: policing and patrolling; caring and rescuing; and observing and knowing. The lines between the three are blurred and have been interwoven to the extent that “illegality is not just produced but productive”.

In Senegal, local police are partners – and beneficiaries – of the European border regime, monitoring the migrant situation on the ground. At the same time, aid agencies and governments routinely convene to push the need for funding sensitisation workshops about the dangers of migration and for support to returned migrants. Controlling migration has become a business that survives on its own failure; every new illegal migration crisis brings further funding commitments and justifications for its continued operation. For example, the Spanish government’s decision to double aid to sub-Saharan Africa from 2006-2010 was influenced by the 2006 influx of migrants.

Andersson moves on to critique three absurd aspects of this migration industry. Firstly, European borders are guarded by some of the most high-tech surveillance, which is entirely disproportionate to the perceived threat. Secondly, physical barriers that have been erected to protect borders – six-metre barbed-wire fences around Spain’s Moroccan enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla – exist in a world where such delineations are increasingly irrelevant. Finally, the threat posed by ‘illegal’ migrants is overstated: they make up less than 1% of overall migratory flows for Spain.

He argues that deterrents are not only ineffective and expensive but actually “generate more illegality”. Money would be better spent in addressing the push and pull factors that encourage migration at source. Until the root causes are addressed, the migrants will keep coming.

In the final section of his book, Andersson takes time to explain the situation facing migrants who make it to Ceuta and Melilla. In providing insight into the life they lead in controlled camps with limited freedoms, he seeks to create empathy from the reader with those stranded on the border.

The argument is clearly stated and well-researched. It calls into question the relevance of an industry that, as 2014 showed, has failed to contain the flow of migration to Europe. The multi-sited ethnographic research model employed to follow transnational patterns enables Andersson to follow the migrants, drawing out the workings of the industry in the process. This provides a rich tapestry of oral testimony that not only makes the reading experience more enjoyable and human, but underpins an emotional and compelling argument.

More discussion about the role of African government interactions with the industry would add value as would a look in more detail at the smugglers who are a hidden part of the process. But that might need another book and ultimately these are minor quibbles that should not detract from what is an excellent account.

In short, Andersson argues for a dismantling of the “illegal industry” and for the reader to see and understand migration for what it is, nothing more than people on the move. I would highly recommend this debut book. It is accessible to readers with a general interest in the subject but still offers plenty for those at the policy level to consider. In offering a challenge to conventional thinking it delivers an argument that is politically powerful.

This review was originally published on Africa at LSE, and is reposted here with permission. Jamie Hitchen is a Policy Researcher at the Africa Research Institute.