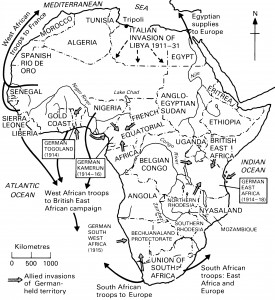

The first shot fired by a British unit in World War I came from the rifle of an African soldier – Regimental Sergeant-Major Alhaji Grunshi of the Gold Coast Regiment – as an Anglo-French force invaded the German colony of Togoland (today’s Togo) on 7 August 1914. The last surrender of German troops took place in Northern Rhodesia (Zambia) on 25 November 1918, two weeks after the Armistice in Europe.

PHOTO: Palgrave Macmillan, History of Africa (3rd ed) – Map 23.2 The First World War and Africa, 1914–18

This summer the centenary of the outbreak of “the war to end war” will be commemorated throughout Europe. The scale of human suffering and loss of life during the conflict will loom large everywhere. But one important theatre of war is likely to remain largely overlooked – Africa.

This cannot be explained by the size of the butcher’s bill. In the eastern Africa campaign, by far the largest and longest of four fought on the continent, the official death toll among British combatant and support units exceeded 105,000 men. The true figure was undoubtedly much higher. Even as it stood, it equalled the tally of American war deaths. It was almost double the number of Australian or Canadian or Indian troops who gave their lives in the Great War. At least one in every eight adult males in British East Africa (Kenya) died in the fighting between 1914 and 1918.

The conflict in eastern Africa was as mobile as the war in Europe was static and, in the words of one soldier, “involved having to fight nature in a mood that very few have experienced and will scarcely believe”. These two characteristics accounted for the high casualties. As supplies of livestock could not match the depredations of disease, the burden for providing transport fell on a resource that was available in sufficient quantities – human beings. The vast majority of war deaths were among carrier units.

In sub-Saharan Africa as a whole the death toll was 1.5 – 2 million.

It was not uncommon for troops and carriers to march 20 miles a day for a month or more in searing heat or torrential rain, with minimal rations and negligible medical resources. While the voices of the campaign were mostly European, there is little doubt that African combatants would have concurred with the sentiment expressed by a young British lieutenant who, in 1914, had witnessed the slaughter in the trenches of the Western Front of every single man in his half-battalion, yet wrote to his mother from East Africa, 16 months later, “I would rather be in France than here”.

In 1919, George Beer, Chief of the Colonial Division of the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, remarked that he had “not seen the tale of native victims [of the fighting] in any official publication” and speculated that “it may be too long to give to the world and Africa”.

Also read: Princes’ Progress: Reconstruction and authority in Eritrea and Rwanda

The civilian populations of eastern Africa suffered privation on a scale unimaginable in all but a few pockets of Europe. By the end of 1915 not a single community in a region much larger than France and the German Reich combined was left untouched by the war. In German East Africa – Tanzania –the colonial troops routinely appropriated crops and animals without payment and impressed some 300,000 men, women and children for carrier duty. In some parts of the country, sowing and harvesting became impossible in 1916-17 as 150,000 Allied troops criss-crossed it in pursuit of a fragmented German force barely one seventh the size.

In 1917-18 famine inevitably struck much of eastern Africa. Moving elsewhere in search of relief was not an option for civilians. There was none, and worse was to come. In autumn 1918 the Spanish influenza epidemic – the “disease of the wind” – spread rapidly along the supply lines of troops scattered across the region. In British East Africa 200,000 people – one tenth of the total population died – in a couple of months.

One phrase is common to many oral histories of the epidemic: “there came a darkness”. In sub-Saharan Africa as a whole the death toll was 1.5 – 2 million. This was the final, most diabolical, tragedy to accompany the “White Man’s Palaver” on the continent.

The conflagration in eastern Africa did not affect the outcome of the main “show” in Europe. But as the final phase of the “scramble for Africa” by European powers, it epitomised the vainglorious imperial ambitions which helped to trigger – and certainly prolonged – World War I. At the Pan-African Conference in 1919, William DuBois, the prominent African American activist and founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, remarked that “in a very real sense” imperial rivalries in Africa had been “a prime cause” of the war and lamented the consequences, namely that “twenty centuries after Christ, black Africa, prostrate, raped and shamed, lies at the feet of the conquering Philistines of Europe”.

Where the campaign in eastern Africa has entered the public consciousness in Europe, it is usually through fiction. CS Forester’s The African Queen, Wilbur Smith’s Shout at the Devil and William Boyd’s An Ice Cream War all capture its absurdity (in very different ways). But in this centenary year the courage, suffering and sacrifice of those – combatant and non-combatant alike – caught up in what one historian has termed this “maelstrom of gigantic proportions” in Africa should also be remembered.

By Edward Paice, Director, Africa Research Institute

This article was first published on The Africa Report.